|

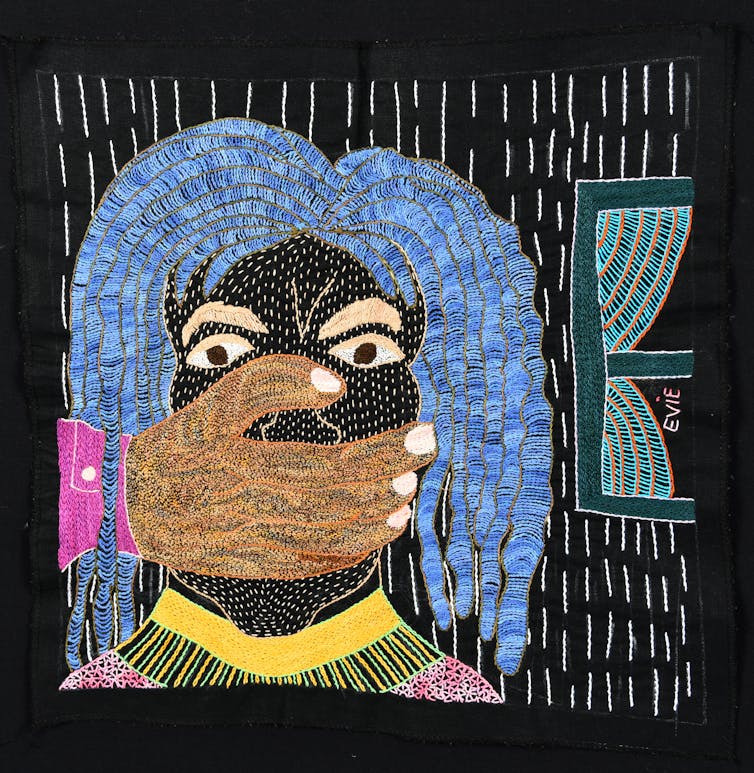

| In her artwork for the project, Christine Leputla depicted victims of domestic violence fleeing their attacker |

By Puleng Segalo, University of South Africa

In June 2020, three months after South Africa entered the first of a series of hard lockdowns to slow the spread of COVID, the country’s president Cyril Ramaphosa described men’s violence against women as a “second pandemic”.

In the first three weeks of that lockdown the Gender Based Violence Command Centre, designed to support victims of gender-based violence (GBV), recorded more than 120,000 victims. Also in its 2019/2020 crimes statistics, the South African Police Services indicated that an average of 116 rape cases were reported each day.

While South Africa’s GBV crisis is not new, it was exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, which made the perpetual challenges faced by many women and gender non-conforming individuals hyper visible.

This visibility sheds light on the reality that the home is a complex space where care and violence can co-exist. Women can feel simultaneously safe and in danger in their homes. All of this happens behind closed doors, often robbing women of a voice to express their fear, suffering and pain.

That affects more than just individual women: GBV is a collective, structural challenge. When women are violated at homes, it affects familial relations, productivity at work, and overall societal functioning.

I am a psychologist who wanted to harness the power of visual artistic expression to highlight the multi-layered ways in which gendered violence is woven into everyday encounters. To do so, I turned – as I have done in previous research – to embroidery.

As I have written in my previous research into the role of embroidery in empowering women’s storytelling, for this current work, I drew again from this methodology to visually tell the narrative of GBV in colourful and creative ways, paying attention to moments of encounters where those who perpetrate and those against whom the violence is perpetrated appear in the same frame. The visual artwork invites the viewer to witness. The hope is that beyond the witnessing is a call for action.

Everyday violence

Beyond making visually appealing artwork, needlework has always been a useful tool to tell difficult or unspeakable stories. Through depicting their lived experiences of gender trauma, women can have an outlet for their pain. While their embroideries serve as a canvas for the outpouring of pain, loss and trauma, their work also tells stories of hope, resilience and resistance.

For this research I worked with the Intuthuko women’s collective. The group consists of 16 Black women based in one of the townships (these are historically Black urban residential areas) in Ekurhuleni in the Gauteng province. GBV in South Africa continues to affect Black women disproportionately, a reality rooted in history as well as in present systems.

The idea with this project was to let the visuals do the talking. So we did not focus on personal experiences, but an overview of the many ways in which GBV shows itself in our lives. I was part of the group and also contributed in making an embroidery piece. This allowed me to shift from being just a researcher and spectator to becoming a contributor in the process of thinking, reflecting and making. It was a collaborative endeavour where we came up with themes as a collective and then each focused on a particular theme for the making of the embroideries.

During the process of making the embroideries, we would share stories of how GBV constantly affects our communities, reflecting on the need to use these embroideries as a form of awareness raising, tool for community dialogues, and to challenge the patriarchal system that has rendered the world unsafe for women.

The aim was to highlight the multi-layered ways in which gendered violence is woven into everyday encounters. We sought to engage the ways in which creative meaning could be made of GBV in our communities – and how the challenges facing our society because of gendered violence could be given attention.

Perpetual fear

The embroideries depict a society where fear is manufactured, created, and produced by patriarchal and unjust structural violent systems. This in turn leads to women living in perpetual fear; they cannot feel safe within and outside of their homes.

Through our artistic visual depictions, we expressed how GBV creates a sense of women being regulated and controlled, and of not entirely owning their bodies.

Some embroideries featured women being violated and robbed in public places, reduced to kneeling down for mercy. The artworks highlighted women’s sense that the streets are not safe and that they are never sure whether they will make it back home safely.

Feeling unsafe and in a constant state of fear makes it difficult for many women to exercise their agency: when society is structured in ways that make women victims, patriarchy prevails.

Staring reality in the face

These embroideries are not just pieces of visual art. They are a challenge to the viewer to stare the violence in the face with the hope that they will be compelled to reflect and to act.

The embroideries have been displayed at an art exhibition where the public could attend and engage with the pieces. We also produced a multilingual visual booklet which is being used in the women’s community and schools as a tool for opening up dialogues on GBV.![]()

Puleng Segalo, Chief Albert Luthuli Research Chair, University of South Africa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.