| |

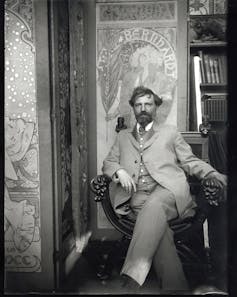

| Jimmy Donegan's painting, Papa Tjukurpa Pukara, depicts andcestral stories. Jimmy Donegan/AAP |

By Joshua Waters, Deakin University

First Nations peoples have been present on the Australian continent for more than 65,000 years. During this time, they have managed to develop and maintain continuous, unbroken connections with the land, water and sky.

Understanding the deep interrelatedness between humans and their (human and nonhuman) kin and ancestors instilled a sense of responsibility, through custodianship of their environment. The aim of this was to survive, and to promote a sense of ecological and cosmological balance.

Indigenous Australian spiritualities understand this balance, which is essential to living in harmony with all things in creation.

More than two-thirds of young Australians are experiencing eco-anxiety, while almost half of Australians believe our country is in “decline”. First Nations spiritualities may have some answers.

Dreaming Ancestors

Australia’s more than 250 different First Nations language groups are connected by various elements of spirituality.

In a general sense, spirituality captures the relationship between self, others and “God”.

In an Indigenous context, spirituality is the basis of First Nations peoples’ existence. Essentially, it is a way of life that informs their relationships with all of creation, including plant and animal kin.

The notion of creation itself is informed by cosmologies that are specific to each group. A deeply seeded belief in creative forces that have shaped – and continue to shape – all things is personified as Dreaming Ancestors.

These entities can take many forms and pervade all parts of the universe. They are also said to exist in “time outside of time”, otherwise known as The Dreaming.

The presence of these entities, along with the paths they travelled, the conflict and interactions they experienced, and in some cases, their subsequent deaths, scored Earth’s surface.

The areas and landmarks they occupied in The Dreaming are now depicted as sacred or culturally significant places. The memory of their existence is honoured through rituals and ceremonies that hold the laws and customs for each community.

Cultural practices such as stories, songs and dances have been used as memory aids to transmit knowledge across thousands of generations, and to maintain the Laws and customs handed down by each Dreaming Ancestor.

Kombumerri and Mununjahli law scholar Christine Black suggests these cosmologies define First Nations peoples’ principles, ideals, values and philosophies. In turn, this promotes an overarching Law of Relationship, which teaches us about the importance of Aboriginal protocols for promoting balance and harmony, while also honouring diversity and relational interconnectedness across species.

Songlines, which intersect and connect across the entire continent, support individual groups in trading materials and intellectual properties, propagating spiritual practices and processes that centre social and ecological health.

Maintaining balance and harmony

Despite the vast differences between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, the primary aim of their spiritualities tends toward developing, maintaining and sustaining cosmological order through balance and harmony.

Balance as a dynamic, fluctuating process plays a crucial role in the workings of the universe. This is also true for many of the fundamental laws of physics, as well as the human body, and at quantum levels. This concept is also reflected in First Nations Australian languages.

Warraimaay historian Victoria Grieves-Williams describes how Yarralin people of the Central Northwest area of the Northern Territory say a person is “punyu” when they are feeling fully alive. This means they are good, happy, strong, healthy, smart, responsible, beautiful and clean.

Similarly, punyu can also refer to the time when people burn off the tall grass in the correct season. Yarralin peoples describe the application of cultural burning in this way as making the country “happy to be taken care of” and “clean and good”.

Australian anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose suggested when the cosmos is punyu, it is homeostatic. This means it is always working towards perfect balance and harmony, of which humans may be regarded as key facilitators (custodians).

Grieves-Williams extends this notion of homeostasis to capture balance in relation to the human body, too. This suggests punyu is the closest word for the caretaking of living systems (both personal and planetary), health and the overall functions of wellbeing.

Australia’s ability to connect with First Nations spiritualities through Indigenous cosmologies may be a doorway into finding deeper meaning in ourselves and the universe – and the vital role of humans as a custodial species and facilitators of a greater cosmological order.

Rekindling our connections

First Nations spirituality promotes a strong sense of interrelatedness and interconnectedness between all things, particularly people and the planet.

Aboriginal Elders have told us we are a reflection of the Country: if the land is sick, so are we. If the land is healthy (or punyu), so are we. Wik First Nations scholar Tyson Yunkaporta says our collective wellbeing can only be sustained through a life of communication with a sentient landscape and all things on it.

In a time when we as a global human population are navigating the complex challenges of modernity, an immersion into First Nations’ spirituality may help us better live in harmony with all things – and importantly, ourselves and each other.

We can explore the depths of these teachings and learn to appreciate them (rather than appropriating them) by reconnecting with the land in meaningful ways, under the guidance of First Nations Elders and Traditional Custodians.

![]()

Joshua Waters, Senior Research Fellow, Indigenous Knowledges, Deakin University