|

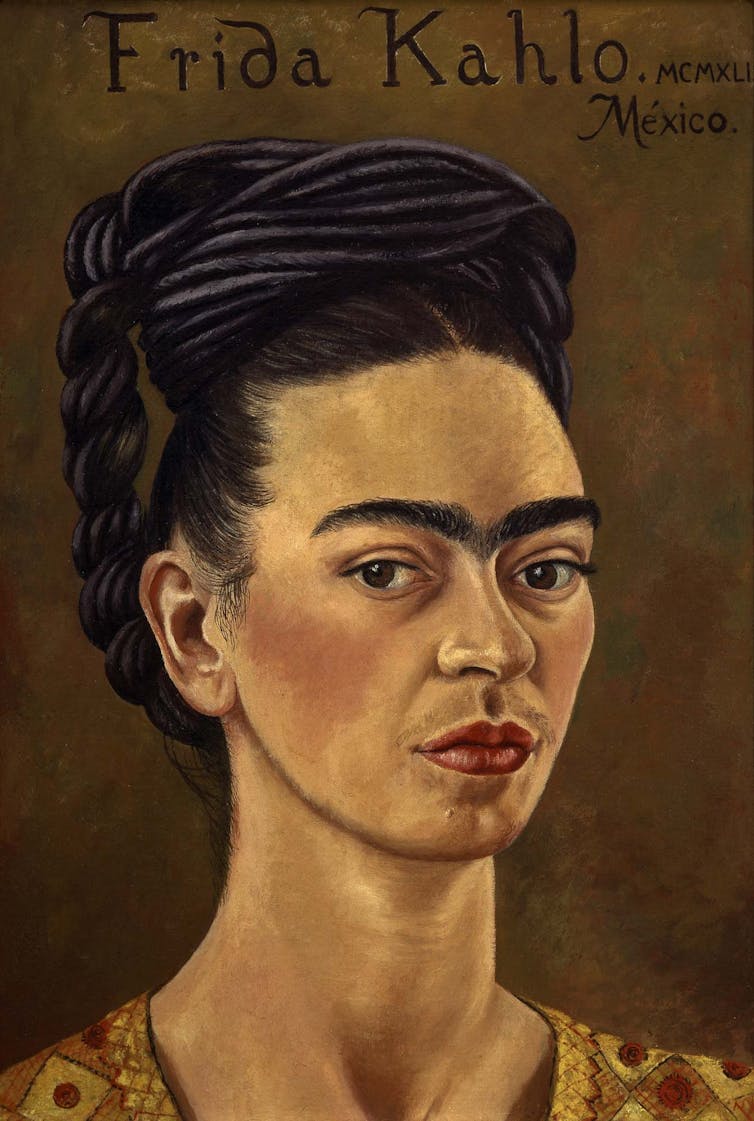

| Feathery creations made from fabric, with no wastage, and hand-made ceramic jewellery designed by Yuima Nakazato and shown in Paris. Cover picture and main photograph above by Elli Ioannou. |

The fusion of futuristic technology and craftsmanship is at

the heart of Yuima Nakazato's groundbreaking new haute couture collection.

Drawing inspiration from his transformative journey through Kenya last year, the designer was

profoundly moved by the sight of mountains of garbage, starkly juxtaposed

against the raw beauty of the African landscape. Reporting by Antonio Visconti. Story by Jeanne-Marie Cilento. Photography by Elli Ioannou, Andrea Heinsohn, Patrick Marion and Anna Nguyen

|

Called Magma, Yuima Nakazato's atmospheric haute couture show. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn

|

Yuima Nakazato's new collection is another creative exploration of his experiences in Kenya, highlighting the urgent need for environmental consciousness and reimagining fashion's role in contributing to a better future.

The epiphany the Japanese designer had in Africa about the scale of textile waste was examined, through a different lense, in last season's collection too.

Nakazato is challenging traditional notions of producing fashion and encouraging conservation and social change. The designer's 14th collection was presented in Paris at the Palais de Tokyo with an atmospheric show in a darkened space with suggestive hovering black "clouds" and a brilliant, red-lit floor covered in Nakazato's print of the piles of abstracted garbage that looked like a fiery landscape.

The first few minutes of the show were silent, except for the evocative clinking of the designer's hand-made, ceramic jewellery, worn like elegant sashes slung across one shoulder, and falling to the waist. A mesmerizing soundtrack was introduced that added to the sombre yet beautiful presentation.

Nakazato is challenging traditional notions of producing fashion, highlighting the urgent need for conservation and social change

|

The clinking, red ceramic jewellery made by the designer. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

Inspired by ornaments worn by African tribes, the jewellery is made of thousands of ceramic pieces, each hand made by Yuima Nakazato in his atelier. These were then crocheted together with bright-red twine to form what the designer calls "acoustic ceramic dresses," creating the ethereal sound at the beginning of the Paris presentation.

The red ceramic pieces made a striking contrast to the silky, black designs created by the designer's revolutionary Type-1 construction, where the garments are riveted together rather than sewn with a needle and thread. These fluid, draped pieces were like wearable staples amid the more dramatic, conceptual designs.

Larger, jewellery pieces like abstracted exoskeletons and oyster shells were worn with long, dark capes and tunics, making a strong visual statement.

Ankle-length skirts, dustcoats and the suspended ceramic pieces, some like lilies curling around the neck, kept to the tripartite palette: black, red and white. Diaphanous prints in black and white provided a lighter and airier note to the tenebrous ambiance.

A crinkled, strapless gown, the colour of parched earth, and a ruched jacket in the form of a Renaissance doublet, were made with a textile that had a three-dimensional affect. Brilliant red prints made by Nakazato of conceptual images of garbage were on flowing robes and highlighted against black. Some were like tribal robes or flung over the shoulder, like contemporary urban warriors walking across the desert.

Inspired by ornaments worn by African tribes, the jewellery is made of thousands of ceramic pieces, each hand-made by Yuima Nakazato in his atelier

|

The voluminous yet airy and light concoction in faux feathers. Photograph: Patrick Marion |

A feathery, voluminous concoction in white with a large, sculptural neckpiece added an otherworldly note of drama along with the sparkling eyeshadow drawn across the forehead.

Shimmering in deep reds, another striking design with faux feathers above a ruched skirt was like an exotic bird. with sparkling red across the brow.

Leaving no wastage of material, the feather like pieces of fabric were cut out with no material remaining from the roll.

As a counterpoint to the distinctive red and black looks were romantic gowns with rippling fabric gathered and cinched at the waist by large, ceramic sculptural buckles and with attenuated reds becoming white, on long skirts.

Looking like a young chieftain, a model with a bare chest except for a totemic necklace and diaphanous feathered cape in red with a white stripe, made another connection with the African landscape.

A feathery, voluminous concoction in white with a large. sculptural neckpiece added an otherworldly note of drama

|

The 3D textile created using brewed protein fabric and digital printing. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

The flower-like confection of look 29 was created using Yuima Nakazato's "brewed protein" fabric made by Japan's Spiber Inc, that he has experimented with in other collections, and which shrinks when in contact with water.

An extraordinary three-dimensional textile is created from a rectangular piece of fabric by controlling the shrinkage with digital printing technology.

As noted by the designer, his travels in Kenya, did affect his creative vision over the past two haute couture seasons. The scale of the waste he encountered left an indelible mark on his consciousness, including the hellish images of fires amid plastic trash and noxious odors.

It was like a bleak portrayal of the end of the world, leaving the designer with a desire to not only evoke change but feeling compelled to find a way to reimagine the landscape's ugliness and transform it into something meaningful with this new collection.

"The shocking experiences I had during my 2022 visit to Kenya still remain vivid in my mind to this day" he explains. "Among the many memories I have of that time, the mountains of garbage I saw are particularly hard to forget. The spontaneous flames, the reeking odors, the garish colors of the plastic trash ~ it seemed like the end of the world, and it left my head spinning."

"The shocking experiences I had during my 2022 visit to Kenya still remain vivid in my mind to this day."

|

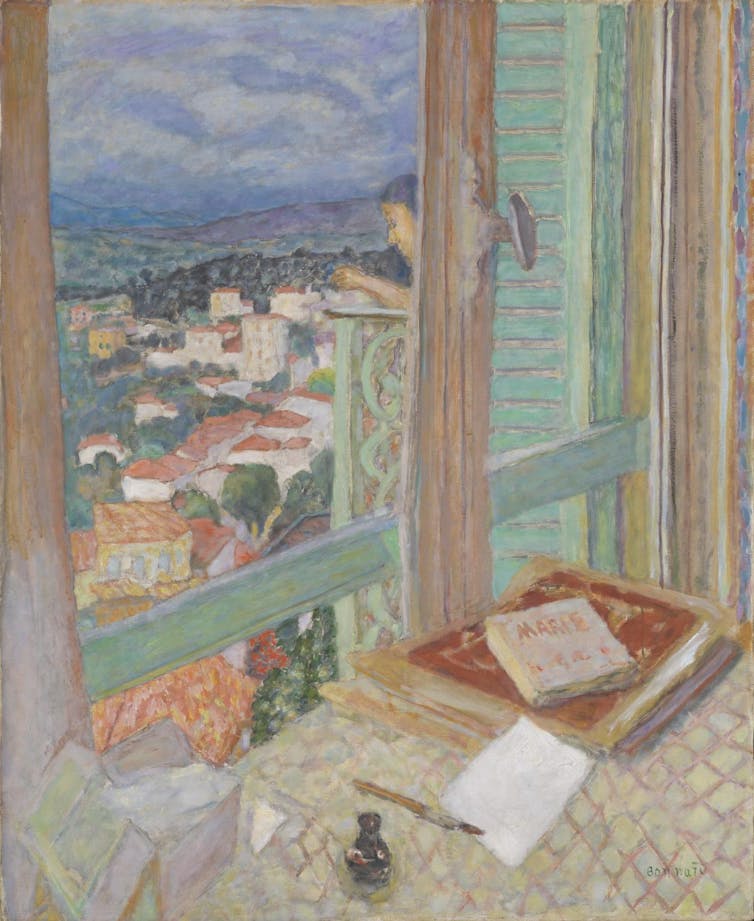

The "awful scenery" which Nakazato transformed into an abstract landscapte for this fiery red print. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn |

His memories of the experience are deeply ingrained, particularly the haunting images of piles of textile waste which have informed both this collection and last season.

The new work has subsumed more of his intital shock and he has approached the theme this time in a more philosophical way.

"I saw a piece by Hokusai commonly known as "Aka-Fuji" at an art gallery," the designers says. "This scene of Fuji recalled to mind thoughts of the magma sleeping within the mountain, and somehow made me aware not only of its beauty, but also of the spooky nature of the landscape as well.

"Using a photo, I had taken while in Kenya, I graded it all in red and printed it out on a piece of fabric. Suddenly, the awful scenery became abstract, and the mounds of manmade garbage somehow turned into something almost like a landscape. At that moment, I realized that it was possible to reconsider the essential meaning of a thing, thereby endowing it with a new meaning and an entirely different value. "

"The spontaneous flames, the reeking odors, the garish colors of the plastic trash ~ it seemed like the end of the world, and it left my head spinning."

|

Cinched at the waist by sculptural, ceramic belt buckles, this diaphanous gown has a delicate attentuation of red to white. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

Choosing the color red as a symbol of transformation, Nakazato employs it to express his conviction that there is a path to changing the future. He redefines red as a catalyst for positive change and a call to action.

"Red usually represents warning or crises," he says. "However, rather than viewing it as an alert to the environmental issues facing us today, I've chosen to put my belief in the color and use it to express my conviction that there is a way for us to change the future."

Central to the creation of the Magma collection was the recycling of 150kg of used clothing brought back from Africa that he was also able to use in his previous collection.

The challenge of recycling clothes without proper labels, so the origin and type of material remain unknown, was overcome with Seiko Epson's dry fibre technology.

Nakazato describes the process as "rescuing clothes that had nowhere else to go," and transforming them into new textiles for the creation of innovative garments.

With this collection, Nakazato defies conventional fashion norms and empowers the industry to embrace sustainability and social responsibility. By repurposing used clothing, utilizing cutting-edge technologies, and drawing inspiration from nature and cultural heritage.

"I've chosen to put my belief in the color and use it to express my conviction that there is a way for us to change the future."

|

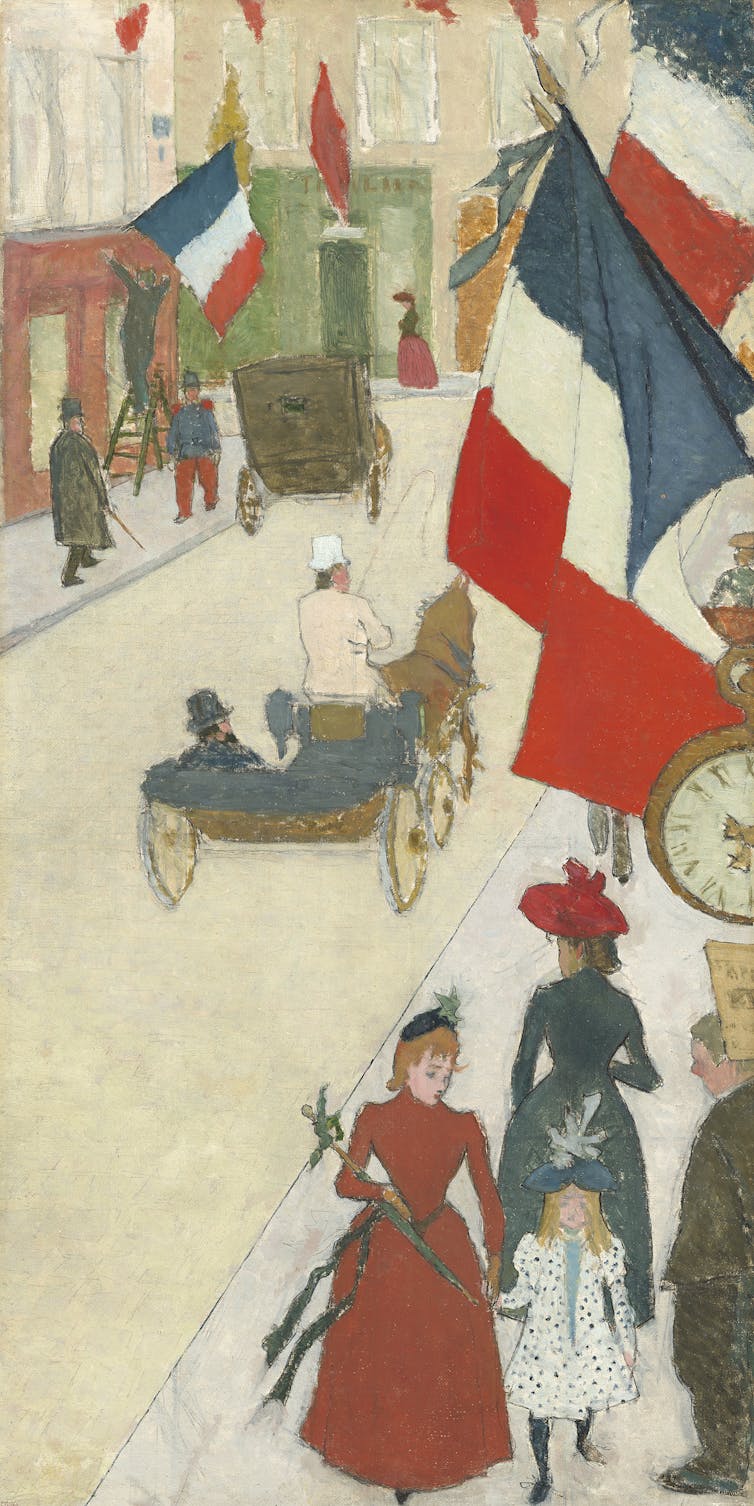

The haute couture presentation at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, was enveloping and atmospheric. Photograph: Patrick Marion |

Nakazato challenges the fashion world to adopt a new perspective ~ one that prioritizes the creation of an improved environment through the way garments are designed and produced.

Seiko Epson's digital textile printing technology also played an important role in translating Nakazato's impressions of Africa onto fabric.

The photographs taken amidst the mountains of garbage became the foundation for installations at the shows, symbolizing Earth's destruction caused by humanity's hand. This expression of devastation serves as a reminder of the urgent need to address these issues.

To infuse the collection with a sense of authenticity, Nakazato's team ground stones from East Africa's largest desert into nano-size natural pigments. These pigments were then used to dye the synthetic brewed protein materials developed by Spiber Inc, resulting inresonant earthy hues woven into the fabrics.

Nakazato challenges the fashion world to adopt a new perspective, the creation of an improved environment through the way garments are designed and produced

|

Designer Yuima Nakazato takes his bow at the end of his show in Paris. Photograph; Anna Nguyen |

Like last season, Nakazato drew inspiration from the traditional costumes of tribespeople in Northern Kenya, incorporating their wrapping techniques and reinterpreting fashion's approach to size and gender.

His latest collection exemplifies the designer's commitment to addressing social issues and driving change through fashion. By transforming used clothing into new textiles, utilizing cutting-edge research, and incorporating elements inspired by Africa's landscapes and tribal history, Nakazato presents a vision of a more hopeful fate for humanity and the planet.

Through his thought-provoking designs and experiments with producing new textiles, Nakazato asks the industry to reevaluate its practices and embrace the power of fashion as a catalyst for change.

Highlights of Yuima Nakazato's Haute Couture AW 2023-24 Collection

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou

|

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais De Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

| Backstage Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

| Backstage, detail of the hand-made ceramic jewellery, Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

Backstage Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou

|

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Patrick Marion |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Patrick Marion |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Elli Ioannou |

|

| Detail Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Patrick Marion |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24. Palais de Tokyo, Paris, Photograph; Patrick Marion |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Torkyo, Paris. Photograph: Anna Nguyen |

|

| Yuima Nakazato Haute Couture Autumn/Winter 2023-24, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Photograph: Andrea Heinsohn. |

![]()