|

| Newspaper headlines when Trump wins the Presidency, as read on the subway, created by Barry Blitt and published in the New Yorker, November 14, 2016. |

Like many, I entered The New Yorker through the cartoon door. The first cartoon I loved, and remember to this day, featured a New Yorker staple – two guys sitting in a bar – with one saying to the other: “I wish just once someone would say to me, ‘I read your latest ad, and I loved it’.”

For someone whose first job after university was an unhappy stint in an advertising agency, the cartoon was a tonic. They are still the first thing I look at when the magazine arrives by mail or the daily newsletter by email, and the first thing shared with my family. There have been around 80,000 published since the magazine’s first issue on February 25 1925.

I had discovered The New Yorker while studying literature at Monash University and writing an honours thesis on the playwright Tom Stoppard. The English drama critic Kenneth Tynan had written a long profile of Stoppard for the magazine in 1977, combining sharp insights into the plays, behind-the-curtains material from Tynan’s time as literary manager at the National Theatre (he bought the rights to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead in 1966) and slices of Stoppard’s life.

The most enticing of these was Tynan’s account of a Saturday afternoon cricket match between a team from The Guardian, comprising several no-nonsense typesetters and the paper’s industrial correspondent, and Harold Pinter’s XI, which was actually a IX owing to two late withdrawals, including the captain himself.

Stoppard arrived in dazzlingly white whites but didn’t seem to take the game seriously, inadvertently dropping a smouldering cigarette butt between kneepad and trousers as he took the field. “Playwright Bursts into Flames at Wicket,” he called back to Tynan standing on the boundary.

Once the game began, though, Stoppard was a revelation, first as wicket-keeper where his “elastic leaps and hair-trigger reflexes” saw him dismiss four players, and then as a batsman, when he smoothly drove and cut his way to the winning score.

I had never read anything like this. It wasn’t academic literary criticism, which tended to assault the English language on a polysyllabic basis. It wasn’t the daily newspaper, which as Stoppard himself mocked, was terse, formal and leaned to the formulaic. It wasn’t a biography of someone long dead, but a “profile”, whatever that was, of a living, breathing person.

I wanted more and so began looking out for the magazine but read it only intermittently. Released from advertising, I began working in journalism in 1981. The 1980s coincided with the final years of William Shawn’s 35-year editorship when The New Yorker almost collapsed under the weight of very long articles about very slight subjects and Shawn’s legendary prudishness. (Tynan once referred to a “pissoir”, which Shawn changed to “circular curbside construction”.)

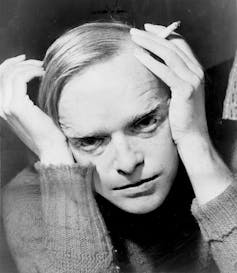

Shawn began working at The New Yorker as a fact-checker eight years after its founding in 1925 by Harold Ross, a former newspaperman, and his wife, reporter Jane Grant. Shawn took over as editor after Ross’s death in 1951, and was brilliant, encouraging writers such as Rachel Carson, James Baldwin, Hannah Arendt and Truman Capote to do work better than even they expected.

More than 60 writers have dedicated books to Shawn that grew out of New Yorker articles, according to Ben Yagoda’s excellent 2000 history of the magazine.

In Shawn’s later years, though, the weaknesses of his approach became dominant, and he could not bear to let go of the editorship. As John Bennet, a staff member trying to decipher Shawn’s gnomic utterances, said:

Shawn ran the magazine the way Algerian terrorist cells were organised in the battle of Algiers – no one knew who anybody else was or what anybody else was doing.

Yagoda writes the cornerstones of the magazine were:

A belief in civility, a respect for privacy, a striving for clear and accurate prose, a determination to publish what one believes in, irrespective of public opinion and commercial concerns, and a sense that The New Yorker was something special, something other and somehow more important than just another magazine. These admirable values all had their origin in the Ross years. But under Shawn, such emotional energy was invested in each of them that they became obsessive and sometimes distorted and perverted, in the sense of being turned completely inward.

The 1980s may have been a difficult period for the magazine, but it still produced some outstanding journalism, and it was the journalism I increasingly turned to, particularly that of Janet Malcolm. Today, readers know of her work through books such as In the Freud Archives, The Journalist and the Murderer and The Silent Woman, but all three, like most of her writing, originally appeared as long articles in the magazine.

I can still recall the jolt I felt reading the famous opening paragraph of The Journalist and the Murderer (published in the magazine in 1989):

Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.

Malcolm’s dissection of the relationship between Jeffrey MacDonald, a convicted murderer, and Joe McGinniss, a journalist convicted by her ice-cold, surgically precise prose, is by turns brilliant, thought-provoking, infuriating and incomplete. Well over three decades later, Malcolm’s book is one all journalists should read.

To Malcolm, the relationship between journalists and their subjects was the “canker that lies at the heart of the rose of journalism”, which could not be rooted out. Hers was a long overdue wake-up call for an industry allergic to reflection and self-criticism. But in the end, for all the brilliance with which she opened up a difficult topic, Malcolm packed the journalist–subject relationship in too small a box.

Among her colleagues at the magazine were many who carefully and ethically navigated the challenges of gaining a subject’s trust, then writing about them honestly, as I learnt when researching a PhD which became a book, Telling True Stories.

One example is Lawrence Wright’s work for the magazine on the rise of Al-Qaeda, and the subsequent book The Loooming Tower. In a note on sources, Wright reflects on the questions of trust and friendship that haunt the journalist–subject relationship.

Knowledge is seductive; the reporter wants to know, and the more he knows, the more interesting he becomes to the source. There are few forces in human nature more powerful than the desire to be understood; journalism couldn’t exist without it.

By conspicuously placing a tape recorder between him and his interviewee, Wright tries to remind both parties “that there is a third party in the room, the eventual reader”.

Outstanding journalists

When I began teaching journalism, especially feature writing, at RMIT in the 1990s, I found myself drawn more and more to The New Yorker and to its history. The “comic paper” Ross originally envisaged had travelled a long way since 1925. The second world war impelled Ross and Shawn, then his deputy, to broaden and deepen the scope of their reporting.

Most famously, after the dropping of two atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, forcing the Japanese to surrender in 1945, they commissioned John Hersey to return to Japan, interview survivors and, as Hersey later put it, write about “what happened not to buildings but to human beings”. Ross set aside the cartoons and devoted the entire issue of August 31 1946 to Hersey’s 31,000-word article simply headlined “Hiroshima”.

I still remember being deeply moved by “Hiroshima”, which I first read half a century after publication and half a world away while on a summer holiday in the bush. The backstory behind the article (ranked number one on the Best American Journalism of the 20th Century list), and its impact on journalism and the world, is well told in Lesley Blume’s 2020 book, Fallout.

By the 1990s, when Tina Brown became the first woman to edit The New Yorker, it definitely needed a makeover. It still did not have a table of contents, nor run photographs. And, beyond a headline, it gave readers little idea what a story was about! She eased up on the copy editors’ notorious fussiness. As E.B. White, a longtime contributor, once said: “Commas in The New Yorker fall with the precision of knives in a circus act, outlining the victim.”

Brown lasted only marginally longer than her predecessor, Robert Gottlieb. Her editorship has been given a bad rap by New Yorker traditionalists, but she gave the magazine a much-needed electric shock, injecting fresh blood.

A list of outstanding journalists she hired who remain at the magazine three decades later is illuminating: David Remnick (who followed her as editor, in 1998), Malcolm Gladwell, Jane Mayer, Lawrence Wright, Anthony Lane and John Lahr, among others.

There’s going to be a lot of celebrating of the magazine’s 100th anniversary, including a Netflix documentary scheduled for release later in the year.

Not many magazines reach such a milestone. One of The New Yorker’s early competitors, Time, which began two years before, was for many years one of the most widely read and respected magazines in the world. It continues today but has a thinner print product and a barely noticed online presence. (I say that as someone who once worked for three years in Time’s Australian office.)

Time is far from alone in this. Magazines, like newspapers, have struggled to adapt to the digital world as the advertising revenue that once afforded them plump profits was funnelled into the big online technology companies, Google and Facebook.

Yet The New Yorker has not only adapted to the digital age but thrived in it. It is one of few legacy media outlets whose prestige and influence have actually grown in the past two decades.

As the internet arrived, the New Yorker’s paid circulation was 900,000. It exceeded a million, for the first time in the magazine’s history, in 2004. As of October last year it was 1,161,064 (for both the print and electronic edition). Subscribers to the magazine’s electronic edition have increased five-fold since it began in 2016 and now stand at 534,287. Yes, advertising revenue remains challenged, recently forcing some redundancies at the magazine, but nothing compared to other parts of the media industry.

Apart from the weekly edition, a daily newsletter was introduced around 2015. The magazine has also expanded into audio, podcasting and documentary film, runs a well-attended annual festival, invites readers to try their hand at devising captions for cartoons and does a line of merchandising. All the astute branding on the part of the magazine and its owners, Condé Nast, would have Shawn rolling in his grave, but the core of the magazine’s editorial mission remains true.

Why it succeeds

The key reasons behind The New Yorker’s current success, in my view, are twofold. First, as the internet made a cornucopia of information available instantly anywhere, the magazine continued to produce material, especially journalism, that was distinctive and different.

Think, for example, of the extraordinary disclosures made by Seymour Hersh and Jane Mayer during George W. Bush’s administration (2001–2009) about the torture by American soldiers of Iraqi prisoners in Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison and how rules about what constituted torture were changed to make almost anything short of death permissible.

Both journalists later published their work in books: Hersh’s Chain of Command: the road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib (2004) and Mayer’s The Dark Side: the inside story on how the war on terror turned into a war on American ideals (2008).

Alongside the investigative journalism have been many examples of deep, productive dives into seemingly unpromising topics such as the packaged ice cube business (Peter Boyer, The Emperor of Ice, February 12 2001) and a movie dog (Susan Orlean, The Dog Star: the life and times of Rin Tin Tin, August 29 2011).

In a world of information abundance, what remained scarce was the ability to make sense of chaotic events, knotty issues and complicated people, in prose that is almost always clear, alive to irony, elegant and sometimes profound. In other words, while most of the legacy media was dumbing down, The New Yorker was dumbing up.

The second reason for the magazine’s continued success is that even as the internet’s information abundance has curdled into the chaos and cruelty of social media’s algorithm-driven world, The New Yorker has not wavered in its editorial mission.

Just as Donald Trump doubled down on the Big Lie surrounding the 2020 election result and the January 6 2021 riots at the Capitol, so the magazine doubled down on reporting his actions since then and into his second presidency.

Other media outlets, even The Washington Post, which did so much excellent reporting during the first Trump presidency, have kowtowed to Trump, or at least its proprietor appears to have. Jeff Bezos decided the newspaper should not run a pre-election endorsement editorial last year. The Amazon owner was placed front and centre with other heads of the big tech companies at Trump’s inauguration on January 20.

By contrast, The New Yorker has published a steady stream of reporting and commentary about the outrageous and shocking actions of the Trump administration in its first month.

The new administration has moved so quickly and on so many fronts that the import of its actions have overwhelmed the media, making it hard to keep up with reporting every development in the detail it might deserve.

To take one example, The Washington Post reported that candidates for senior posts in intelligence and law enforcement were being asked so-called loyalty questions about whether the 2020 presidential election was “stolen” and the January 6 Capitol riots an “inside job”.

Two individuals being considered for positions in intelligence “who did not give the desired straight "yes” answers, were not selected. It is not clear whether other factors contributed to the decision".

The report prompted media commentary, but not enough of it recognised the gravity of an attempt to rewrite history every bit as egregious as Stalinist Russia.

The New Yorker has made its own statement, in response, by reprinting Luke Mogelson’s remarkable reporting from January 6 2021, with photography by Balasz Gardi and alarming footage from inside the capitol with the rioters.

David Remnick, now in his 27th year as editor, was among ten media figures asked recently by The Washington Post how the second Trump administration should be reported. He said:

To some degree, we should be self-critical, but we should stop apologizing for everything we do. I think that journalism during the first Trump administration achieved an enormous amount in terms of its investigative reporting. And if we’re going to go into a mode where we’re doing nothing but apologizing and falling into a faint and accepting a false picture of reality because we think that’s what fairness demands, then I think we’re making an enormous mistake. I just don’t think we should throw up our hands and accede to reality as it is seen through the lens of Donald Trump.

Remnick’s argument is clear-eyed and courageous. You would hope it is heard by other parts of the news media that have long ceded editorial leadership to what was for many years categorised simply as a “general interest magazine”.

Failing that, they could look at the cartoons. On February 14, the magazine published one by Brendan Loper featuring a drawing of Sesame Street’s Cookie Monster standing outside the Cookie Company factory where a spokesman said,

Let me assure you that as an unpaid “special factory employee” Mr. Monster stands to personally gain nothing from this work.

Here’s looking at you, Elon.![]()

Matthew Ricketson, Professor of Communication, Deakin University