By Darius von Guttner Sporzynski

Following the death of Pope Francis, we’ll soon be seeing a new leader in the Vatican. The conclave – a strictly confidential gathering of Roman Catholic cardinals – is due to meet in a matter of weeks to elect a new earthly head.

The word conclave is derived from the Latin con (together) and clāvis (key). It means “a locked room” or “chamber”, reflecting its historical use to describe the locked gathering of cardinals to elect a pope.

Held in the Sistine Chapel, the meeting follows a centuries-old process designed to ensure secrecy and prayerful deliberation. A two-thirds majority vote will be needed to successfully elect the 267th pope.

History of the conclave

The formalised papal conclave dates back centuries. And various popes have shaped the process in response to the church’s needs.

In the 13th century, for example, Pope Gregory X introduced strict regulations to prevent unduly long elections.

Pope Gregory X brought in the rules to prevent a repeat of his own experience. The conclave that elected him in September 1271 (following the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268) lasted almost three years.

Further adjustments were made to streamline the process and emphasise secrecy, culminating in Pope John Paul II’s 1996 constitution, Universi Dominici gregis (The Lord’s whole flock). This document set the modern framework for the conclave.

In 2007 and 2013, Benedict XVI reiterated that a two-thirds majority of written votes would be required to elect a new pope. He also reaffirmed penalties for breaches of secrecy.

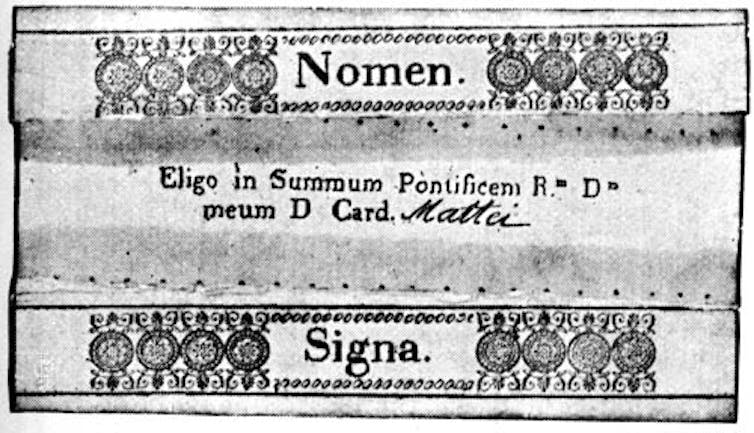

The secrecy surrounding the conclave ensures the casting of ballots remains confidential, and without any external interference.

The last known attempt at external interference in a papal conclave occurred in 1903 when Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria sought to prevent the election of Cardinal Mariano Rampolla. However, the assembled cardinals rejected this intervention, asserting the independence of the electoral process.

How does voting work?

The conclave formally begins between 15 and 20 days after the papal vacancy, but can start earlier if all cardinals eligible to vote have arrived. Logistical details, such as the funeral rites for the deceased pope, can also influence the overall timeline.

Historically, the exact number of votes required to elect a new pope has fluctuated. Under current rules, a minimum two-thirds majority is needed. If multiple rounds of balloting fail to yield a result, the process can continue for days, or even weeks.

After every few inconclusive rounds, cardinals pause for prayer and reflection. This process continues until one candidate receives the two-thirds majority required to win. The final candidates do not vote for themselves in the decisive round.

How is voting kept secret?

The papal conclave is entirely closed to the public. Voting is conducted by secret ballot within the Sistine Chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the pope’s official residence.

During the conclave, the Sistine Chapel is sealed off from outside communication. No cameras are allowed, and there is no live broadcast.

The cardinals involved swear an oath of absolute secrecy, and face the threat of excommunication if it is violated. This ensures all discussions and voting remain strictly confidential.

The iconic white smoke, produced by burning ballots once a pope has been chosen, is the only public signal that the election has concluded.

Who can be elected?

Only cardinals who are under 80 years of age at the time of conclave’s commencement can vote. Older cardinals are free to attend preparatory meetings, but can not cast ballots.

While the total number of electors is intended to not exceed 120, the fluctuating nature of cardinal appointments, as well as age restrictions, make it difficult to predict the exact number of eligible voters at any given conclave.

Technically, any baptised Catholic man can be elected pope. In practice, however, the College of Cardinals traditionally chooses one of its own members. Electing an “outsider” is extremely rare, and has not occurred in modern times.

What makes a good candidate?

When faced with criticism from a member of the public about his weight, John XXIII (who was pope from 1958-1963) retorted the papal conclave was “not a exactly beauty contest”.

Merit, theological understanding, administrative skill and global perspective matter greatly. But there is also a collegial element – something of a “popularity” factor. It is an election, after all.

Cardinals discuss the church’s current priorities – be they evangelisation strategies, administrative reforms or pastoral concerns – before settling on the individual they believe is best suited to lead.

The cardinal electors seek someone who can unify the faithful, navigate modern challenges and maintain doctrinal continuity.

Controversies and criticisms

The conclave process has faced criticism for its strict secrecy, which can foster speculation about potential “politicking”.

Critics argue a tightly controlled environment might not reflect the broader concerns of the global church.

Some have also questioned whether age limits on voting cardinals limit the wisdom and experience found among older members.

Nonetheless, defenders maintain that secrecy encourages free and sincere deliberation, minimising external pressure and allowing cardinals to choose the best leader without fear of reprisal, or of public opinion swaying the vote.

Challenges facing the new pope

The next pope will inherit a mixed situation: a church that has grown stronger in certain areas under Francis, yet which grapples with internal divisions and external challenges.

Like other religions, the church faces secularisation, issues with financial transparency and a waning following in some parts of the globe.

One of the earliest trials faced by the new pope will be unifying the global Catholic community around a shared vision – an obstacle almost every pope has faced. Striking the right balance between doctrine and pastoral sensitivity remains crucial.

Addressing sexual abuse scandals and their aftermath will require decisive action, transparency and continued pastoral care for survivors.

Practical concerns also loom large. The new pope will have to manage the Vatican bureaucracy and interfaith relations, while maintaining the church’s stance on global crises such as migration and poverty – two issues on which Francis insisted mercy could not be optional.

The cardinal electors have a tough decision ahead of them. The Catholic community can only pray that, through their deliberations, they identify a shepherd who can guide the church through the complexities of the modern world.![]()

Darius von Guttner Sporzynski, Historian, Australian Catholic Universit