|

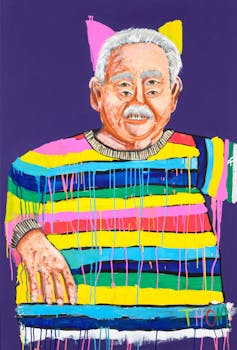

| Winner Archibald Prize 2024, Laura Jones, Tim Winton, oil on linen,

198 x 152.5 cm. © the artist, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Jenni

Carter |

By Joanna Mendelssohn, The University of Melbourne

In awarding this year’s Archibald Prize to Laura Jones’ portrait of the writer Tim Winton, the Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales are doing what they do best: catapulting a relatively unknown artist to instant fame and possible fortune.

Her portrait of Winton is a study of a man in emotional pain, as he contemplates the possible futures of the world around him.

One of the great disadvantages of being a writer or an artist is that they can see what politicians do not: the long-term consequences of abusing the environment. Both Winton the subject and Jones the artist see our planet is on a path to environmental doom.

Jones met Winton when she was undertaking a residency to study the bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef, so it is appropriate the tones she has chosen as the background to his portrait are dull and muted like a degraded world.

Most of the painting is thinly painted with the exception of his face. This gives the portrait an extra impact.

Although Laura Jones has been a finalist in four previous Archibald Prize exhibitions and has exhibited widely, her profile indicates the only significant collection to hold her work is Artbank, the collection of the Australian government.

That is all about to change.

In what may be a coincidence, another exhibition on the same floor is a solo exhibition by a previous Archibald winner, Wendy Sharpe, whose painterly approach is similar to Jones.

Sharpe’s work not only relates to Jones’ painting in style, but also the circumstance of her winning the prize. In 1996, Sharpe was a relatively unknown artist when she too was awarded the Archibald Prize. The prize was the trigger for a career that has included a stint of being a Gallery Trustee.

The Archibald really does sprinkle fairy dust.

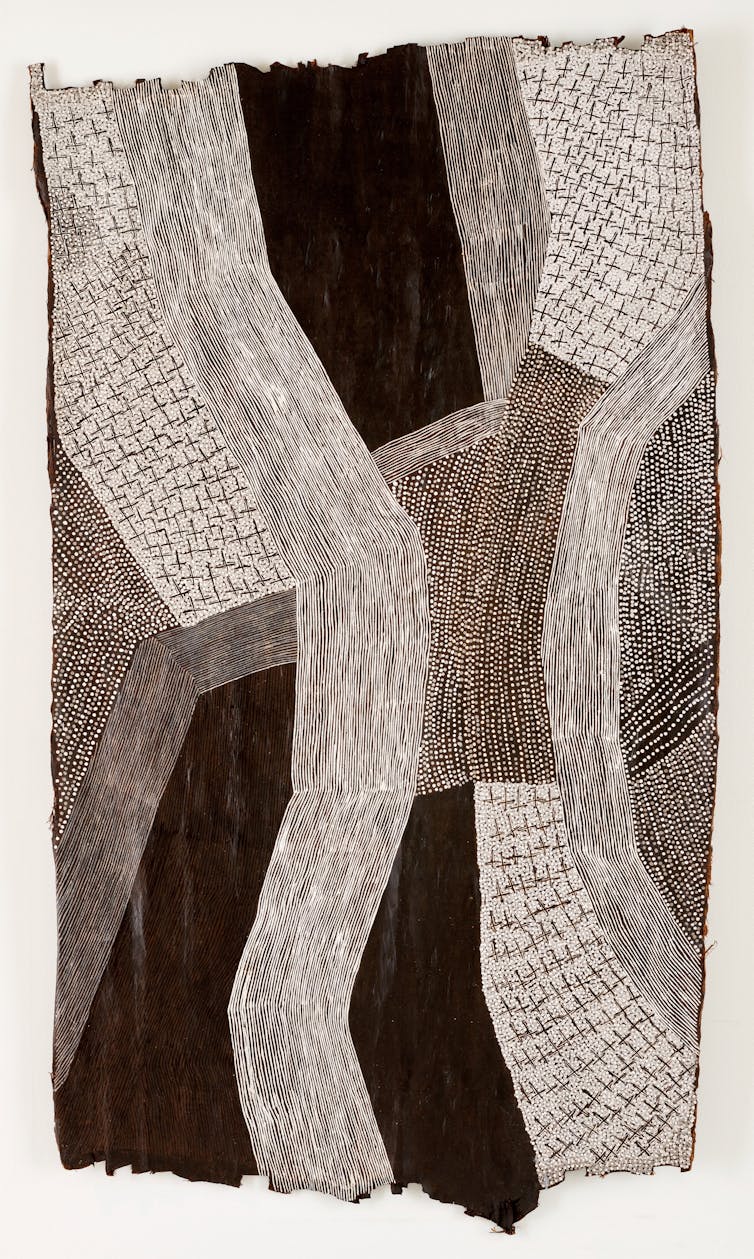

Djakaŋu Yunupiŋu wins the Wynne Prize

When the board president of the trustees, David Gonski, announced the Wynne Prize he took great joy in noting this year the majority of the entrants selected for hanging were Aboriginal artists.

Awarded to “the best landscape painting of Australian scenery in oils or watercolours or for the best example of figure sculpture by Australian artists”, this oldest of all Australian art prizes has come a long way from when it was dominated by paintings of gum trees in pastoral landscapes.

Djakaŋu Yunupiŋu’s painting, Nyalala gurmilili, is a celebration of sunrise in Miḏawarr (the harvest season following the wet) when sudden showers surprise during the day.

It is probably the largest bark painting to be exhibited in the gallery, a glorious undulating pattern of rhythms and shapes.

There is a special significance in this artist being awarded the prize for this work at this gallery.

Many years ago her father, Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu, was one of a group of Yolngu elders who sat with the gallery’s assistant director, Tony Tuckson, and showed him the connection between painting and lore. Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu’s bark paintings are among the treasures of the Art Gallery of NSW’s collection.

Naomi Kantjuriny wins the Sulman Prize

Unlike the Archibald and Wynne Prizes, which are judged by the trustees, the Sulman Prize for best subject painting, genre painting or mural project has a single judge, usually an artist.

This means every year the exhibition has a different flavour, reflecting the judge’s taste. This year’s judge, Tom Polo, selected an exhibition ranging from the traditional formalism of David Eastwood to the conceptual humour of Kenny Pittock.

He has awarded the prize to Naomi Kantjuriny for her painting Minyma mamu tjuta, from the Tjala Arts Centre. She has described her painting as being about the stories told and her culture.

It is a lively painting of spirits, good and bad, dancing in the land, gathering around people, always present.

The Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 2024 are on display at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, until September 8.![]()

Joanna Mendelssohn, Honorary (Senior Fellow) School of Culture and Communication University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.