|

| Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon. Photograph: courtesy of Apple |

By Joan Tumblety, University of Southampton

Directors of historical feature films face a difficult task. How can they make the characters familiar to an audience without reducing them to caricature? How can they make sure that knowledge of the outcome – battles won or lost, empires built then ruined – doesn’t make the story seem like it’s writing itself?

Director Ridley Scott is not a historian and presumably wants to entertain rather than to enlighten. But the problem of historical truth is an interesting one.

It is not easy to know the “real” Napoleon. There’s a recognisable version of him – the confident general beloved of his troops, the instinctive military tactician who could run on empty for days at a time, his stern and somewhat petulant gaze. But much of this is the product of layers of historical storytelling, accrued by the labour of generations of artists, journalists and memoirists – and of course, Napoleon himself.

Abel Gance’s spectacular silent film Napoleon (1927), for example, charted the life and career of Napoleon up to his departure as a military general for the Italian campaign in 1796. In one scene, a heavy winter snowfall interrupts classes at Napoleon’s military college. The boys run outside to play and inevitably start throwing snowballs at each other. The scene depicts a very young Napoleon emerging as a natural commander, directing the combat as though on the field of battle.

Yet the veracity of this moment rests primarily on a single account – the memoir of one of Napoleon’s childhood friends, Louis de Bourrienne, who attended the same school. The author was later an employee of Napoleon, who sacked him for embezzlement in 1802.

Many years later, in 1829, de Bourrienne penned a memoir in the hope of cashing in on the popular appetite for authentic tales of the great general. What we think we know about the “real” Napoleon is often filtered through self-interested and partial accounts like this one.

Here are the facts and legends behind some of the major scenes from Ridley Scott’s new Napoleon biopic.

Did Napoleon crown himself?

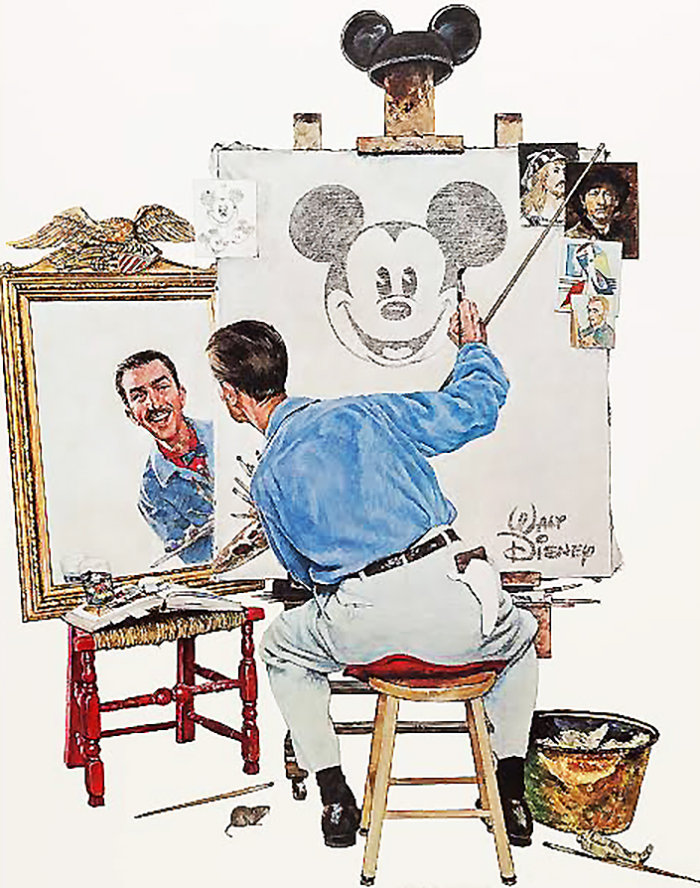

Napoleon went to great lengths to craft his image as a benign ruler and man of the people, often enlisting the talents of artists to do so.

Most notoriously, Jacques-Louis David was commissioned to produce a series of grand paintings depicting Napoleon’s coronation in Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris in December 1804. In the most famous, we see Napoleon place a crown on the head of the new Empress Josephine while a reluctant Pope Pius VII looks on.

In an astonishing act of hubris, Napoleon had indeed already placed a crown on his own head, though the oil painting shows him only in laurel leaves to signify his martial triumphs. What Scott’s film depicts is the magnificence of the oil paintings, which showed Napoleon and his empress in the most flattering light, rather than the coronation ceremony itself.

His relationship with Josephine

There is no doubt that Napoleon felt a deep passion for Marie Joséphe Rose de la Pagerie – known to him as Joséphine – whom he married in 1796 as his military career was in the ascendant. Yet her depiction in Ridley Scott’s film as a young seductress probably speaks more to sexist cliche than to Joséphine’s undoubted self-assuredness.

She was six years older than Napoleon, a widow and mother of two young children when they met, and the young general’s romantic feelings were seemingly stronger than hers. While on campaign he wrote to her virtually every day, his pen sometimes piercing the parchment, such was the force of his emotions. Yet some of these letters to her remained unopened.

Their relationship was as tumultuous as it was passionate, and both spouses had several affairs. Yet when Napoleon instigated divorce in 1809 for want of an heir, it was surprisingly amicable. The Empress retained her imperial title until her death in 1814 and was permitted to continue living in the imperial Château de Malmaison.

Was Napoleon present at the execution of Marie Antoinette?

The autumn of 1793 was especially busy for Napoleon given his increasingly important role in the Siege of Toulon. Federalist rebels had handed over the French fleet to the British admiral Samuel Hood, and the young artillery officer commanded the operation that eventually seized it back.

Therefore it is highly unlikely that he ventured to Paris in October to be among the crowd that witnessed the execution of Queen Marie-Antoinette.

In a letter to his older brother Joseph, however, Napoleon did claim to witness the storming of the Tuileries Palace by an angry crowd of republican protesters in June 1792. It revolted him.

Did Napoleon really fire at the pyramids?

Napoleon began his Egyptian campaign in 1798. The cultural legacy of the campaign can be seen in the well-stocked Egyptology section of the Louvre. But it was also the scene of atrocities.

At one point, several thousand Ottoman soldiers were shot or driven into the sea on Napoleon’s orders, rather than taken prisoner. You don’t need to invent ice traps or Napoleon ordering his men to fire at the pyramids, as Ridley Scott’s biopic does, to convey his callous disregard for life.

It was the rumour that he had ordered his own plague-stricken troops to be poisoned in the town of Jaffa that finally tarnished Napoleon’s reputation in the early 19th century. It stuck, no matter how brilliant the sanitising riposte of the artist Antoine-Jean Gros, whom Napoleon commissioned in 1804 to paint a different story.

Ridley Scott’s film does not represent the past so much as carry versions of the tales and images depicting Napoleon that have spun him into existence since his own lifetime – many of which were crafted by his own hand.

Joan Tumblety, Associate Professor of French History, University of Southampton