Friday, 22 September 2023

China is Criminalising Clothing ‘Hurtful to the Spirit and Sentiments of the Nation' ~ Could this Mean a Kimono Ban?

|

| Ryo Yokitashi/Unsplash |

By Antonia Finnane, University of Melbourne

In August 2022 a young woman wearing a yukata – a simple, summer-weight kimono – was having her photo taken on a street in picturesque Suzhou, China, when she was accosted by a police officer. Following an angry exchange, partly captured on her phone, she was arrested for disturbing the public peace.

The Suzhou Kimono Incident, as it came to be known, sparked an internet debate over the propriety of wearing kimonos and the legality of the policeman’s actions.

This was not the first time wearing a kimono in China had caused a furore, and it would not be the last. Another broke out in March this year, after a visitor to Nanjing, site of an infamous massacre by the Imperial Japanese Army in 1937, reported seeing a woman in a white kimono posing amidst the cherry blossoms in a Buddhist temple. He complained to the attendants, but they said it was merely a matter of ethics: after all, people were free to wear what they like.

That may soon change. A new draft law on public security published online at the beginning of this month includes a clause criminalising the wearing of clothes that might be “hurtful to the spirit and sentiments of the nation”. If the law is passed, offenders will face penalties of up to 5,000 yuan (A$1,000) and up to 15 days jail.

Draft laws, routinely posted for comment, rarely attract many responses. The response to this one has been huge, with around 100,000 submissions to date. Legal scholars in China have weighed in, pointing out the fuzziness of this clause and its openness to abuse by local law enforcers.

And as one Beijing lawyer intimated, the legislation seems directly aimed at the kimono.

A ‘hurtful’ kimono?

Half a century ago, the target of sartorial struggle in China was “strange clothing and outlandish dress” – tight pants were the example par excellence in the 1960s, succeeded by flares in the 1970s.

Such clothing was associated with the United States, the Soviet Union and Hong Kong, all sink-holes of decadence and natural enemies of China under Mao.

Things have changed. Soviet revisionists have morphed into Russian allies; Hong Kong has been swallowed up by the mainland; and with jeans and t-shirts now ubiquitous in China, the US is no longer open to attack on the sartorial front.

Enter Japan, with its spectacular array of distinctive cultural products, strong youth following across East Asia and a wartime history that since the 1980s has been leveraged to foment nationalism in China.

In 1980, Japanese movie star Nakano Ryoko received a rapturous welcome when she visited China. Over the next few years, Japan inspired and provided training for the first generation of post-Mao fashion designers, who helped lay the foundations for a now-flourishing industry.

In the mid-1980s, a fully accessorised kimono as a symbol of excellence in Japanese design was perfectly acceptable for publication in a Chinese magazine.

Simultaneously, however, a “new remembering” of Japanese wartime atrocities – specifically the Nanjing massacre – was emerging, soon to be endorsed by the ruling Communist Party. By the 1990s, a history that had been buried in the Mao years was being given full play.

All this helps explain the visceral responses to young Chinese women wearing kimonos today.

In April 2009, two high-impact films about the Nanjing massacre were released. Images of Japanese soldiers raping Chinese women were fresh in people’s minds when, in September, young model Ding Beili posted a photo of herself online wearing a kimono. She attracted a storm of criticism.

“With so many countries in the world to pick from,” asked one blogger, “why did she have to pick Japan?”

Why indeed? The answer lies in something else that came to China from Japan: cosplay, popular across East Asia. The girl of the Suzhou Kimono Incident was a cosplayer, performing a role from the Japanese anime Summer Time Rendering. Naturally, cosplayers view Japanese-inspired dress differently from their critics.

Among the great occasions for Chinese cosplay until recently were Japanese-style “summer festivals”, or matsuri. It was for a matsuri in Shanghai that Ding Beili donned a kimono in 2009. Increasingly popular in China in recent years, summer festivals were cancelled in at least seven cities in August 2022 under rising anti-Japanese sentiment.

Adding the US to the mix

The ultra-nationalist Hu Xijin, former editor of the Global Times, has dismissed the issue of the kimono in China as a matter of no consequence. “Little Japan,” in his view, is just “a lackey of the US”.

The US-Japan alliance undoubtedly exacerbates Chinese hostility towards Japan, a country that like Australia is an easier target for payback than the US. China’s response to the new tripartite agreement between Japan, South Korea and the US was to slap a ban on Japanese seafood imports, on stated grounds of health security.

The new draft law against “hurtful” dress was posted soon after the implementation of the seafood ban, leaving observers with a distinct impression of China as a place where people can neither eat Japanese fish nor wear Japanese clothes.

Older people must be reminded of a time half a century ago, when young people wearing “strange clothing and outlandish dress” were attacked on the streets, while seafood was hardly available at all.![]()

Antonia Finnane, Professor (honorary), The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Monday, 18 September 2023

Tuesday, 12 September 2023

Kate Barton is Redefining American Eveningwear with Innovation and Sustainability

|

| Kate Barton's shimmering new SS24 collection with its gleaming accessories and innovative materials, presented in New York. Cover picture by Anna Nguyen |

One of the highlights of New York Fashion Week was the new Spring/Summer 2024 collection by American designer Kate Barton. Her unique blend of innovation, technology, avant-garde draping, and shape engineering has made her sleekly futuristic designs a standout, writes Isabella Lancellotti

|

Glimmering and gossamer-fine, the American designer's take on modern eveningwear |

Barton embraces a fabric-first philosophy that optimizes volume without resorting to unnecessary layering, resulting in a modern classicism that is both elegant and innovative.

What makes Barton's creations exemplary are her materials and craftsmanship. The Spring/Summer 2024 collection features chrome leather accessories and magnetized detachable enhancements, creating the illusion of metal while still ensuring practical wearability.

The introduction of crystal-encrusted sculptural belts adds a touch of opulence and whimsy, seamlessly blending sustainability, creativity, and unapologetic luxury. The designer wants to create a couture aesthetic with inventive sculptural garments, engineered materials, sustainable technology-driven cutting, and fabric manipulation.

What makes Kate Barton's creations exemplary are her fresh ideas, experiments with unusual materials and fine craftsmanship

|

Exquisite draping and new materials make Barton's work a standout. |

During the pandemic, she had limited access to machinery and materials, which drove her to try out unusual materials and sustainable methods.

The designer wants to redefine eveningwear but also advocates for positive change. Her profile has grown inside and outside the fashion world as she gains recognition from her peers and the high-profile women she has designed gowns for, from Heidi Klum and Kat Graham to Paige DeSorbo, and Wallis Day.

Kate Barton's vision for the future of American eveningwear is clear. She is eager to continue explore the nature of luxury fashion, bringing a modern approach not often seen in this sector.

Her approach is refined each collection, as she evinces how new technology and materials can be utilized without compromising on style and luxury.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Monday, 11 September 2023

New York Fashion Week: AREA'S Ready-to-Wear and Couture AW23 Collection

|

| The clever trompe l'oeil fabric made to look like luxurious fur, created by AREA, as part of their new collection, shown at New York Fashion Week. Photographs courtesy of Arena |

|

It looks like fur but is a trompe l'oeil version created by Area |

|

Resin bones encrusted with crystals become part of the fur-printed gown |

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Tuesday, 5 September 2023

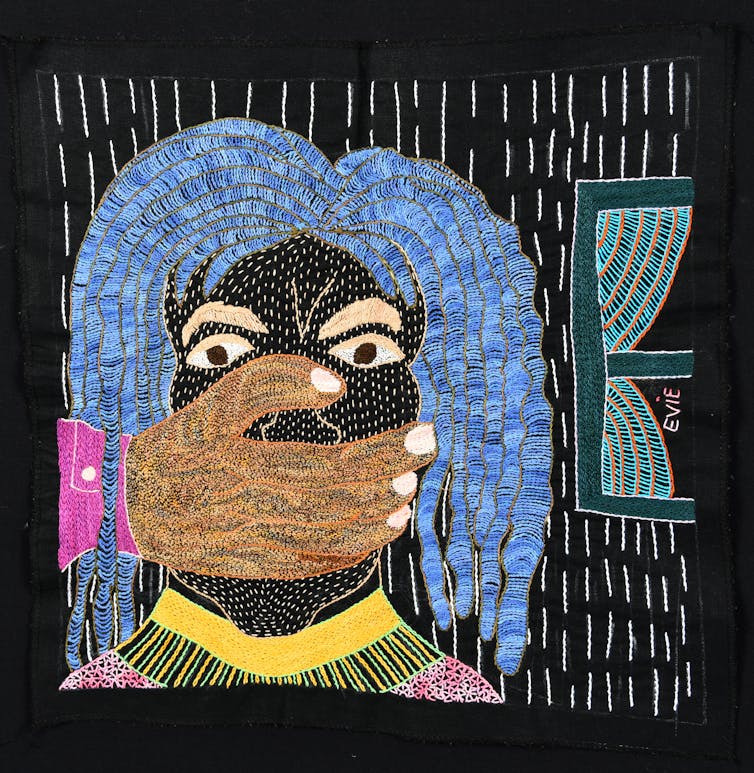

The power of Needlework: How Embroidery is Helping South African Women Tell Their Stories

|

| In her artwork for the project, Christine Leputla depicted victims of domestic violence fleeing their attacker |

By Puleng Segalo, University of South Africa

In June 2020, three months after South Africa entered the first of a series of hard lockdowns to slow the spread of COVID, the country’s president Cyril Ramaphosa described men’s violence against women as a “second pandemic”.

In the first three weeks of that lockdown the Gender Based Violence Command Centre, designed to support victims of gender-based violence (GBV), recorded more than 120,000 victims. Also in its 2019/2020 crimes statistics, the South African Police Services indicated that an average of 116 rape cases were reported each day.

While South Africa’s GBV crisis is not new, it was exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, which made the perpetual challenges faced by many women and gender non-conforming individuals hyper visible.

This visibility sheds light on the reality that the home is a complex space where care and violence can co-exist. Women can feel simultaneously safe and in danger in their homes. All of this happens behind closed doors, often robbing women of a voice to express their fear, suffering and pain.

That affects more than just individual women: GBV is a collective, structural challenge. When women are violated at homes, it affects familial relations, productivity at work, and overall societal functioning.

I am a psychologist who wanted to harness the power of visual artistic expression to highlight the multi-layered ways in which gendered violence is woven into everyday encounters. To do so, I turned – as I have done in previous research – to embroidery.

As I have written in my previous research into the role of embroidery in empowering women’s storytelling, for this current work, I drew again from this methodology to visually tell the narrative of GBV in colourful and creative ways, paying attention to moments of encounters where those who perpetrate and those against whom the violence is perpetrated appear in the same frame. The visual artwork invites the viewer to witness. The hope is that beyond the witnessing is a call for action.

Everyday violence

Beyond making visually appealing artwork, needlework has always been a useful tool to tell difficult or unspeakable stories. Through depicting their lived experiences of gender trauma, women can have an outlet for their pain. While their embroideries serve as a canvas for the outpouring of pain, loss and trauma, their work also tells stories of hope, resilience and resistance.

For this research I worked with the Intuthuko women’s collective. The group consists of 16 Black women based in one of the townships (these are historically Black urban residential areas) in Ekurhuleni in the Gauteng province. GBV in South Africa continues to affect Black women disproportionately, a reality rooted in history as well as in present systems.

The idea with this project was to let the visuals do the talking. So we did not focus on personal experiences, but an overview of the many ways in which GBV shows itself in our lives. I was part of the group and also contributed in making an embroidery piece. This allowed me to shift from being just a researcher and spectator to becoming a contributor in the process of thinking, reflecting and making. It was a collaborative endeavour where we came up with themes as a collective and then each focused on a particular theme for the making of the embroideries.

During the process of making the embroideries, we would share stories of how GBV constantly affects our communities, reflecting on the need to use these embroideries as a form of awareness raising, tool for community dialogues, and to challenge the patriarchal system that has rendered the world unsafe for women.

The aim was to highlight the multi-layered ways in which gendered violence is woven into everyday encounters. We sought to engage the ways in which creative meaning could be made of GBV in our communities – and how the challenges facing our society because of gendered violence could be given attention.

Perpetual fear

The embroideries depict a society where fear is manufactured, created, and produced by patriarchal and unjust structural violent systems. This in turn leads to women living in perpetual fear; they cannot feel safe within and outside of their homes.

Through our artistic visual depictions, we expressed how GBV creates a sense of women being regulated and controlled, and of not entirely owning their bodies.

Some embroideries featured women being violated and robbed in public places, reduced to kneeling down for mercy. The artworks highlighted women’s sense that the streets are not safe and that they are never sure whether they will make it back home safely.

Feeling unsafe and in a constant state of fear makes it difficult for many women to exercise their agency: when society is structured in ways that make women victims, patriarchy prevails.

Staring reality in the face

These embroideries are not just pieces of visual art. They are a challenge to the viewer to stare the violence in the face with the hope that they will be compelled to reflect and to act.

The embroideries have been displayed at an art exhibition where the public could attend and engage with the pieces. We also produced a multilingual visual booklet which is being used in the women’s community and schools as a tool for opening up dialogues on GBV.![]()

Puleng Segalo, Chief Albert Luthuli Research Chair, University of South Africa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Monday, 28 August 2023

Travel: Champagne is Deeply French ~ but the English Invented the Bubbles

|

| Shutterstock |

In 1889, the Syndicat du Commerce des Vins de Champagne produced a pamphlet promoting champagne at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, claiming that Dom Pérignon, procurator of the Benedictine Abbey of Hautvillers from 1668, was the “inventor”, “creator” or discoverer" of sparkling champagne.

“Come, Brothers! I drink stars!” is the famous quote often attributed to him.

The story of a blind monk having an epiphany, accidentally happening upon the secret to effervescence, was seductive. It combined divine revelation and French winemaking expertise to produce a national symbol deeply rooted in the French landscape.

However, the truth is slightly different. Dom Pérignon did contribute to improving the still wines of the Champagne region, but he did not discover effervescence – he was trying to get rid of the bubbles.

The champagne myth

The expo where the champagne myth was propagated marked the 100-year anniversary of Bastille Day and is best known for the debut of another icon of French culture, the Eiffel Tower. The Pérignon story gained traction at the same moment these other symbols of nation-building reinforced the uniqueness of French culture and history.

The basis for the myth can be traced to a letter from Dom Grossard of Hautvillers Abbey to the mayor of Aÿ, in the heart of the Champagne region. Grossard claimed that Pérignon had perfected the method for making perfectly white wine from pinot noir grapes (blanc de noirs), pioneered the technique for effervescence, and championed the use of bottles and corks.

Only the first of these claims is true. At the abbey, wooden stoppers and canvas soaked in grease were used to seal bottles, and French glass was too weak to contain the pressure from effervescence. A bigger problem was that French winemakers – and consumers – considered bubbles a fault, a trick to distract the drinker from bad wine.

Prominent French wine merchant Bertin de Rocheret advised a client who inquired about sparkling wine:

effervescence obscures the best characteristics of good wines, in the same way that it improves wines of lesser quality.

Bubbles, bottles and corks

The method for effervescence, strong glass bottles and the use of corks all came from England in the 17th century. English consumers imported wine in barrels from France because bottles were taxed at a higher rate than wine imported in bulk.

The wines often deteriorated during the journey across the channel and once opened, they oxidised quickly, developing an unpleasant flavour. To improve the taste, consumers added honey, syrup made from raisins or sugar. The additional sugar content caused a secondary fermentation – and effervescence.

In 1662, Christopher Merrett, a founder of the Royal Society, published a paper titled “Some Observations Concerning the Ordering of Wines”, in which he described the method for effervescence:

Our winecoopers of latter times use vast quantities of sugar and molasses to all sorts of wines, to make them drink brisk and sparkling, and to give them spirits, as also to mend their bad tastes.

To produce sparkling wine and retain the effervescence, three things are necessary: bubbles, strong glass bottles and corks.

Merrett’s method provided the fizz, and corks were already used in England for bottling cider and perry. Strong glass in England was a by-product of a prohibition on using wood in industrial furnaces, decreed by King James I in 1615.

Timber was too valuable to be burned for glassmaking, reserved for building ships for the merchant fleet. Using sea coal, English glass furnaces reached higher temperatures and produced stronger glass. These bottles could withstand pressure (as much as a car tyre) without bursting.

The paradox?

The only ingredient the English lacked was wine, prompting French wine historians to refer to their contribution as “The English Paradox”. How could a country with no winemaking tradition pioneer the technique for effervescence? The “paradox” label, however, only makes sense if the traditions and standards of French winemaking are presumed to be superior.

Bound by tradition, French winemakers were unwilling to contemplate a fault as a desirable innovation. Driven by necessity, and without any winemaking rules, English consumers were free to experiment.

But necessity was only part of the equation – English culture did play a part in the success of effervesce. Reserving timber for the English fleet made for stronger glass, and cider and perry production provided corks to seal the bottles.

The French champagne industry now claims effervescence was not invented, but is a natural product of the soil and climate in a strictly defined region.

Natural fermentation does produce some fizz, but rarely enough to pop a cork without the intervention of a winemaker. The emphasis on nature reinforces the exclusivity and unique geographic attributes to distinguish champagne from all other sparkling wines.

A more complex history of the origin of effervescence challenges preconceptions about national identity, even in matters of taste. This does not diminish champagne’s luxury status, but it does reveal the influence of cultural traditions on innovation, and the many influences that pave the way to novelty.![]()

Garritt C Van Dyk, Lecturer, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.