Friday, 3 March 2023

Monday, 27 February 2023

Did pop art have its heyday in the 1960s? Perhaps. But it is also utterly contemporary

Review: Pop Masters: Art from the Mugrabi Collection, New York, HOTA Gallery, Gold Coast, Australia.

Drawn from the private collection of Jose Mugrabi, Pop Masters: Art from the Mugrabi Collection is the first international exhibition presented by HOTA.

It is the strongest signal yet of HOTA’s commitment to investing in a strong and vibrant visual arts community.

The New York-based Mugrabis have been long-term investors in pop art, and the family has the largest Warhol collection outside the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

Emerging in the late 1950s and ‘60s, pop was viewed as a reaction against the lofty ideals of high modernist abstraction practised by artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

Instead, pop art embraced the boom in postwar consumer culture, blurring the conventional hierarchies between high and low art.

Australian audiences have happily displayed an appetite and enthusiasm for major pop art exhibitions. QAGOMA’s Andy Warhol in 2008 and the National Gallery of Victoria’s Basquiat Haring: Crossing Lines in 2019 immediately spring to mind.

Here, curators Tracy Cooper-Lavery and Bradley Vincent have pursued a very different curatorial strategy. As opposed to the deep-dive art-historical investigation, this exhibition advances an argument for the ongoing influence of pop art on contemporary artists today.

Stars of the movement

Organised roughly chronologically, Pop Masters traces six generations of pop art.

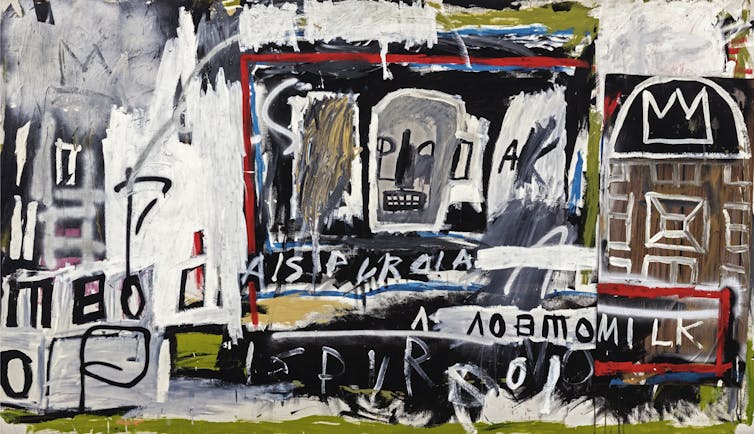

The exhibition turns on a tripartite axis of Warhol, Keith Haring and Jean-Paul Basquiat.

Haring and Basquiat emerged from the streets as graffiti artists, and rose to prominence in the 1980s New York East Village. Both had brief but incredibly productive careers, cut short by HIV-related illness (Haring) and drug overdose (Basquiat).

In 2017, Basquiat reached the dizzying US$100-million-plus club.

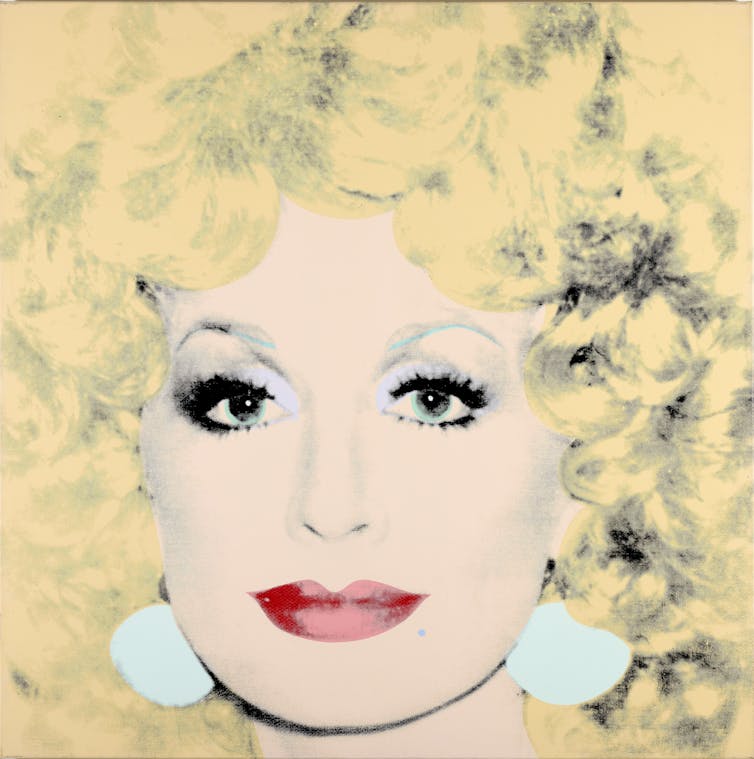

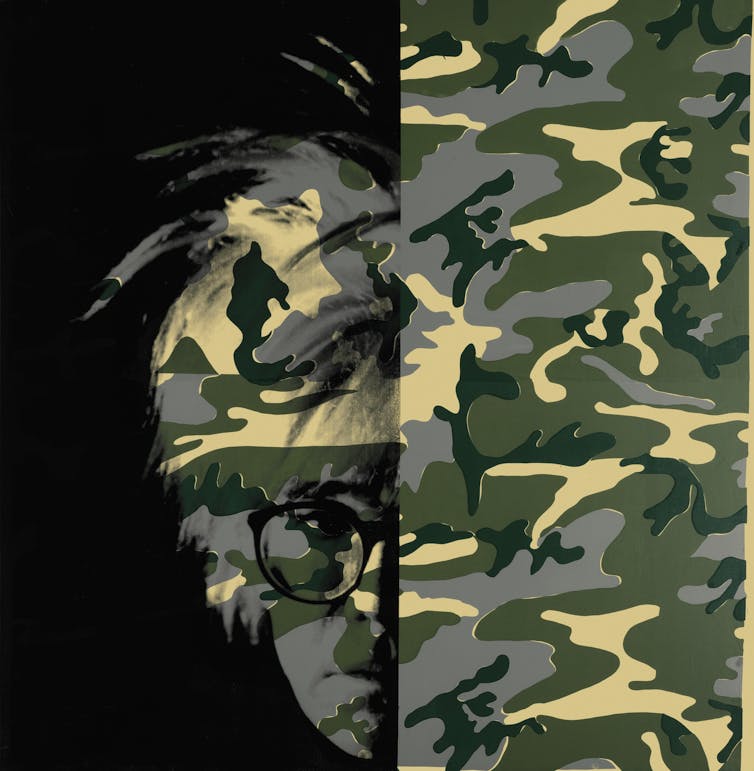

Of the three practitioners, it is Warhol’s name that reverberates well beyond the art world. The exhibition serves as an excellent entry point to understand his enduring influence and legacy.

On display are examples of Warhol’s signature style: photographic silkscreen printing.

Warhol famously appropriated images from media culture. He would reproduce the images using silk screens, placing traditional artistic ideas of skill and creativity under pressure.

Art historians and critics remain divided on the topic of how exactly to read Warhol’s work.

For some, Warhol’s practice deliberately celebrated the vacuity of celebrity and consumer culture. For these critics, there is no point in looking for a “deeper” or “hidden” meaning: it simply does not exist.

Warhol himself certainly encouraged this point of view:

If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.

The alternative argument is advanced by the conviction that Warhol’s practice is deeply political. As opposed to mere surfaces, Warhol’s screenprints are empathetic and urgent responses to the political and social upheavals of the 1960s.

The inclusion of Warhol’s Sixteen Jackies (1964) would support this account: Warhol is mining media images of the First Lady’s grief in the wake of President Kennedy’s assassination.

The debate has never really been settled. As this exhibition would suggest, perhaps Warhol can be both: deeply serious and superficial; political and apolitical; surface and depth.

The following generations

The curators’ underlying argument for the ongoing relevance of pop is bolstered by the inclusion of exciting and diverse contemporary practitioners who are working through the legacies of Haring and Basquiat.

One of the defining characteristics of pop art is the tension between the ordinary and the specialness of the art object.

This tension comes to the fore in Basquiat’s Untitled (Football Helmet) (1981-84). Basquiat painted the football helmet and pasted cuttings of his own hair onto its surface, giving it a comical, whimsical appearance.

Basquiat gave it as a gift to Warhol, reinforcing the collaborative connection shared by the three artists.

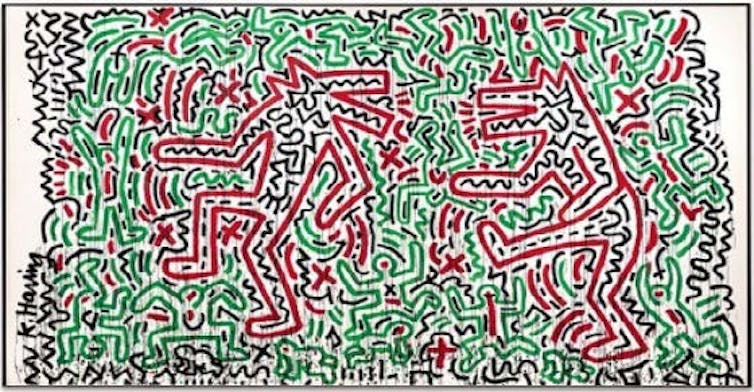

Haring fans are treated to an enormously scaled Untitled (1981) featuring his iconic symbol, the dancing dog. Skipping and gyrating across the canvas, the figures exude trademark Haring: simplified line executed extremely rapidly.

Today, New York-based Katherine Bernhardt establishes a direct visual lineage with Basquiat with her use of spray paint applied directly to the painting’s surface.

Bernhardt works at an enormous scale and includes bananas and everyday objects such as Windex bottles and toothbrushes in a wryly mischievous nod to the still life painting tradition.

Bernhardt is fascinated with how objects might be read as a visual language akin to reading the alphabet. Bernhardt’s Windex bottles extend Haring’s visual symbolism such as his dog and the radiant baby.

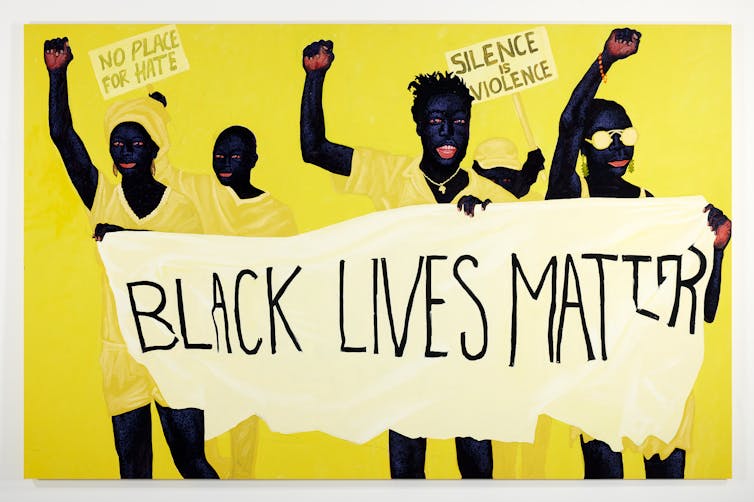

Another welcome inclusion is Ghana-born and based Kwesi Botchway. Primarily a portrait painter, Botchway draws on art’s history of portraiture to document contemporary Ghanaian life.

Botchway’s painting documents the global outpouring of anger and solidarity that followed in the wake of the death of George Floyd in 2020.

By placing Botchway’s blacklivesmatter (Divine Protesting) (2020) in dialogue with Basquiat, we are reminded Basquiat’s practice was deeply political: one of his preoccupations was the representation of race and the African American diasporic communities.

The curatorial argument is clear: pop art is utterly contemporary.

Pop Masters: Art from the Mugrabi Collection New York is at HOTA Gallery, Gold Coast, until June 4.![]()

Chari Larsson is a Senior Lecturer of art history at Griffith University

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Thursday, 23 February 2023

Tuesday, 21 February 2023

Wednesday, 15 February 2023

Saturday, 11 February 2023

Why the discovery of Cleopatra’s tomb would rewrite history

It couldn’t have been a case of better timing. Egyptologists celebrating the centenary of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, now have a promising new archaeological discovery that appears to have been made in Egypt. Excavators have discovered a tunnel under the Taposiris Magna temple, west of the ancient city of Alexandria, which they have suggested could lead to the tomb of Queen Cleopatra. Evidence that this is really the case remains to be seen, but such a discovery would be a major find, with the potential to rewrite what we know about Egypt’s most famous queen.

According to the ancient Greek writer Plutarch – who wrote a biography of Cleopatra’s husband, the Roman general Mark Antony, and is responsible for the lengthiest and most detailed account of the last days of Cleopatra’s reign – both Antony and Cleopatra were buried inside Cleopatra’s mausoleum.

According to Plutarch, on the day that Augustus and his Roman forces invaded Egypt and captured Alexandria, Antony fell on his sword, died in Cleopatra’s arms, and was then interred in the mausoleum. Two weeks later, Cleopatra went to the mausoleum to make offerings and pour libations, and took her own life in a way that is still unknown (a popular misconception is that she was bitten by an asp). She too was then interred in the mausoleum.

In the days that followed, Antony’s son Marcus Antonius Antyllus and Cleopatra’s son Ptolemy XV Caesar (also known as Caesarion, “Little Caesar”), were both murdered by Roman forces, and the two young men may likewise have been interred there.

If the mausoleum of Cleopatra has not already vanished beneath the waves of the Mediterranean along with most of the Hellenistic city of Alexandria, and is one day found, it would be an almost unprecedented archaeological discovery.

A discovery that could rewrite history

While the tombs of many famous historical rulers are still standing – the mausoleum of Augustus, Antony and Cleopatra’s mortal enemy, in Rome, is one example – their contents have often been looted and lost centuries ago.

One notable exception is the tomb of Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, uncovered at Vergina in the late 1970s. The tomb was found intact, and this has enabled decades of scientific investigation into its contents, advancing our knowledge of members of the Macedonian royal family and their court. The same would be true if Cleopatra’s tomb were discovered, and found to be intact.

The amount of new information Egyptologists, classicists, ancient historians, and archaeologists could glean from its contents would be immense. For the most part, our knowledge of Cleopatra and her reign comes from ancient Greek and Roman literary sources, written after her death and inherently hostile to the Egyptian queen. We do not have much evidence revealing the Egyptian perspective on Cleopatra, but what we do have, such as honorific reliefs on the temples that she built and votives dedicated by her subjects, gives us a very different view of her.

The ethics of unearthing Cleopatra’s remains

To date, no other Ptolemaic ruler’s tomb has been found. They were reportedly all situated in the palace quarter of Alexandria and are believed to be under the sea with the rest of that part of the city.

The architecture and material contents of the tomb alone would keep historians busy for decades, and provide unprecedented amounts of information about the Ptolemaic royal cult and the fusion of Macedonian and Egyptian culture. But if Cleopatra’s remains were there too, they could tell us a great deal more, including the cause of her death, her physical appearance, and even answer the thorny question of her race.

But should we be hoping to find Cleopatra’s remains, and to analyse them? From Tutankhamun to the ordinary ancient Egyptians whose mummies have been excavated over the centuries, there has been a long history of mismanagement and mistreatment.

While the days when mummies were unwrapped as a form of entertainment at Victorian dinner parties have thankfully passed, concerns are increasingly being raised by those who work in heritage about the appropriate treatment of our ancestors.

While the discovery of Cleopatra’s tomb would be priceless for Egyptologists and other scholars, is it fair to deny the queen the opportunity for peace and privacy in death that she did not receive in life?![]()

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Friday, 10 February 2023

Want to delete your social media, but can’t bring yourself to do it? Here are some ways to take that step

For more than a decade we’ve been deeply immersed in a love affair with social media. And the thought of ending things can be painful. But like any relationship, if social media is no longer making you happy – and if curating your online persona is exhausting instead of fun – it might be time to say goodbye.

Late last year, Meta (previously Facebook) came under intense scrutiny after leaked documents revealed the company was fully aware of the negative impact its products, Instagram in particular, can have on users’ mental health.

Meta went straight into damage control. But it seemed no one was particularly surprised by the news – not even teenage girls, who Meta identified as most at risk. Was the leak just confirming what we already suspected: that social media has the potential to be much more harmful than helpful?

How did our once carefree relationship with social media turn sour? And perhaps most importantly, can (or should) it be salvaged?

Spotting the red flags

Relationship counsellors will often ask troubled couples to think about what made them happy in their relationship. Social media, for all it’s annoying peccadilloes, does have some redeeming features.

Throughout the pandemic, the ability to stay connected to people we can’t see in person has become incredibly valuable. Social media can also help people find their tribe, particularly if the people in their offline world don’t share their values and beliefs.

But if you can’t go a day without trawling through the sites, feeling compelled to “like” or be “liked”, your relationship is in trouble.

Though far from settled, the bulk of screen time research focuses on the detrimental effects of excessive or problematic screen use on well-being and mental health. A 2021 meta-analysis of 55 studies, with a combined sample size of 80,533 people, found a positive (albeit small) association between depressive symptoms and social media use.

An important finding was that negative consequences were more likely to come from how social media use made participants feel, rather than how long they used it.

Information overload

In trying to understand why social media can leave us feeling less than content, we can’t look past the effect of the 24/7 news (and fake news) stream on our collective psyche.

A 2021 Deloitte survey of Australians found 79% thought fake news was a problem, and only 18% felt information obtained via social media was trustworthy. Having to navigate content that deliberately aims to perpetuate fear and dissent only adds to people’s cognitive and emotional burden.

But here’s the rub. It seems while we’re generally concerned about technology having a negative impact on our well-being, this doesn’t translate to behaviour change on an individual level.

My own research published last year found more than two-thirds of survey participants believed excessive smartphone use can negatively impact well-being, yet individual usage was still very high, averaging 184 minutes per day. There was no relationship between the belief and the behaviour.

What leads to this apparent cognitive-behavioural dissonance? The results of a long-term study by University of Amsterdam researchers might provide a clue. They found living in a “permanently online” world leads to decreased self-control over social media use and, subsequently, lower well-being.

In other words, we know what we’re doing might be bad for us, but we do it anyway.

Simple steps you can take

How do you know when it’s time to reevaluate your relationship with social media? There’s one deceptively simple question to ask yourself: how does it make you feel?

Think about how you feel before, during and after you use social media. If you feel like you’re wasting large chunks of your day, your week (or, dare I say, your life) on social media - that’s a clue. If you feel negative emotions such as sadness, anxiety, guilt or fear, you have your answer.

But if divorcing social media abruptly feels like a step too far, what else can you do to slowly break away, or potentially salvage the relationship?

1. Start with a trial separation

A “soft delete” lets you see how you’ll feel without your social media before committing to a hard delete. Let friends and family know you’re taking a break, remove the apps from your devices, and set yourself a goal of maybe one or two weeks where you don’t access the account/s. If the world is still turning at the end of this trial, keep going! Once you no longer feel the pull of social media, you’ll be ready to hit delete.

2. Reduce the number of platforms you engage with

If you have Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, Snapchat, WhatsApp, Tumblr, Pinterest and Reddit on your phone, tablet and computer, you’re probably past saturation point and into drowning territory. Pick one or two apps that genuinely serve a meaningful purpose for you, and ditch the rest. Gen X’ers find it hard to say goodbye to Facebook, but Gen Zers in the US have largely bid it farewell. If they can do it, so can you!

3. If steps 1 and 2 are still too much, try to reduce your time spent on social media

First and foremost, turn off all your notifications (yes, all of them). If you’re conditioned to respond to every “bing”, you’ll find it almost impossible to stop. Set aside some time each day and do all your social media catching up or browsing. Set an alarm for your predetermined time allocation, and when it sounds, put the phone down until the same time tomorrow.

None of this will be easy, and walking away from social media might hurt at first. But if the relationship has become uncomfortable, or even abusive, it’s time to take a stand. And who knows what untold happiness you might find, beyond the four walls of your screen?![]()

Sharon Horwood, Senior lecturer in Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.