|

| American Vogue editor Anna Wintour at the Met Gala she oversees in New York. Photograph: Charles Sykes/Invision/AP. Cover picture of Stephane Rolland Haute Couture AW25/26 by Jay Zoo for DAM. |

|

Queen Elizabeth II and Anna Wintour at British designer Richard Quinn's 2018 runway show. |

It’s not a retirement, though, as Wintour will maintain a leadership position at global fashion and lifestyle publisher Condé Nast (the owner of Vogue and other publications, such as Vanity Fair and Glamour).

Nonetheless, Wintour’s departure from the US edition of the magazine is a big moment for the fashion industry – one which she has single-handedly changed forever.

Fashion Magazine Fever

Fashion magazines as we know them today were first formalised in the 19th century. They helped establish the “trickle down theory” of fashion, wherein trends were traditionally dictated by certain industry elites, including major magazine editors.

In Australia, getting your hands on a monthly issue meant rare exposure to the latest European or American fashion trends.

Vogue itself was established in New York in 1892 by businessman Arthur Baldwin Turnure. The magazine targeted the city’s elite class, initially covering various aspects of high-society life. In 1909, Vogue was acquired by Condé Nast. From then, the magazine increasingly cemented itself as a cornerstone of the fashion publishing.

The period following the second world war particularly opened the doors to mass fashion consumerism and an expanding fashion magazine culture.

Wintour came on as editor of Vogue in 1988, at which point the magazine became less conservative, and more culturally significant.

Not Afraid to Break the Mould

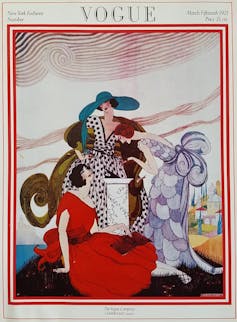

Fashion publishing changed as a result of Wintour’s bold editorial choices – especially when it came to the magazine’s covers. Her choices both reflected, and dictated, shifts in fashion culture.

Wintour’s first cover at Vogue, published in 1988, mixed couture garments (Christian Lacroix) with mainstream brands (stonewashed Guess jeans) – something which had never been done before. It was also the first time a Vogue cover had featured jeans at all – perfectly setting the scene for a long career spent pushing the magazine into new domains.

|

| Anna Wintour's first Vogue cover in November 1988 featuring a revolutionary mix of what we call today hi/o: a Christian Lacroix heavily bejewelled top and a pair of Guess Jeans. |

Wintour’s legacy at Vogue involved elevating fashion from a frivolous runway to a powerful industry, which is not scared to make a statement. Nowhere is this truer than at the Met Gala, which is held each year to celebrate the opening of a new fashion exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute.

The event started as a simple fundraiser for the Met in 1948, before being linked to a fashion exhibit for the first time in 1974.

Wintour took over its organisation in 1995. Her focus on securing exclusive celebrity guests helped propel it to the prestigious event it is today.

This year’s theme for the event was Superfine: Tailoring Black Style. In a time where the US faces great political instability, Wintour was celebrated for her role in helping elevate Black history through the event.

Not Without Controversy

However, while her cultural influence can’t be doubted, Wintour’s legacy at American Vogue is not without fault.

Notably, her ongoing feud with animal rights organisation PETA – due to the her unwavering support for fur – has bubbled in the background since the heydays of the anti-fur movement.

Wintour has been targeted directly by anti-fur activists, both physically (she was hit with a tofu cream pie in 2005 while leaving a Chloe show) and through numerous protests.

This issue was never resolved. Vogue has continued to showcase and feature fur clothing, even as the social license for using animal materials starts to run out.

Fashion continues to grow increasingly political. How magazines such as Vogue will engage with this shift remains to be seen.

A Changing Media Landscape

The rise of fashion blogging in recent decades has led to a wave of fashion influencers, with throngs of followers, who are challenging the unidirectional “trickle-down” structure of the fashion industry.

Today, social media platforms have overtaken traditional media influence both within and outside of fashion. And with this, the power of fashion editors such as Wintour is diminishing significantly.

Many words will flow regarding Wintour’s departure as editor-in-chief, but nowhere near as many as what she oversaw at the helm of the world’s biggest fashion magazine.![]()

Jye Marshall, Lecturer, Fashion Design, School of Design and Architecture, Swinburne University of Technology and Rachel Lamarche-Beauchesne, Senior Lecturer in Fashion Enterprise, Torrens University Australia