By Anne-maree O'Rourke

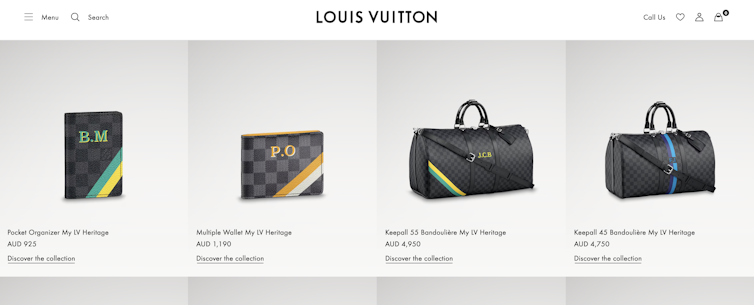

You might think spending $5,000 on a handbag or wallet would be prestigious and exclusive enough. What about taking things one step further – and personalising it with your own name? Brands including Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Dior now offer extensive customisation options – some for a few products, others for their entire range. Names and initials are an obvious, popular choice.

Some have hailed personalisation as the future of luxury goods. But it’s worth asking – could there be any downsides?

Research has shown there’s a trade-off to signalling social status with luxury goods. Luxury consumers are often perceived as less warm and friendly, more concerned with managing their image.

Our recent research examined whether name-stamping could increase this social cost. Our findings suggest for some customers, it can – increasing their fears of being negatively judged.

One-of-a kind products

These personalised touches are marketed as unique, one-of-a-kind products. They’re designed to appeal to a desire for individuality and exclusivity.

For luxury buyers, customisation offers a way to showcase their personality, passions and interests. It can enhance their feelings of connection to a brand and sense of psychological ownership of an item.

Enabling consumers to co-design a product can also help alleviate the impostor syndrome some consumers experience when buying high-end luxury items.

For the brands themselves, personalisation services can increase profit margins, improve market appeal and strengthen customer loyalty.

Much of this trend has been fuelled by millennial and Gen-Z luxury consumers, who are increasingly seeking out unique, tailor-made experiences.

By 2030, it’s expected that millennials and Gen-Z will account for 60–70% of all luxury purchases.

A 2017 survey found more than half of millennials who’d recently made a luxury purchase were willing to pay more for personalised luxury goods.

We love our own names

The popularity of name-stamping, in particular, may come down to a concept called “implicit egotism”.

Research suggests most people have a subconscious positive association with themselves. This extends to a preference for things that are connected to their sense of identity – such as the letters of their own name.

The drawbacks of personalisation are less widely discussed. One clear one is its impact on resale value. Personalised items are harder to sell.

This is particularly relevant for Australia’s booming second-hand luxury market, driven by younger consumers prioritising sustainability and affordability.

Research also suggests that excessive customisation – letting customers make design decisions on custom colours, fabrics, and so on – can decrease the signalling value of luxury items and undermine their status appeal.

Luxury’s social cost

Then there’s the cost that can come with luxury itself.

Research has shown luxury consumers can be perceived as less warm and friendly than those who forgo luxury.

Interestingly, this perception isn’t driven by envy. Rather, it stems from a belief that luxury wearers are actively managing their image to impress others.

Does name-stamping luxury increase this social cost even more? Our research, with co-authors Joanna Lin, Billy Sung and Felix Septianto, suggests the answer is yes.

We conducted four studies with 1,354 female luxury and non-luxury shoppers from the United States.

We found consumers who personalise luxury items with their name worry more about being negatively judged than those who purchase non-customised items.

This effect was consistent, regardless of whether the personalisation featured initials or full first names.

The overtness of name personalisation, in particular, may explain the added social cost. Customising a bag with a non-standard colour might only catch the eye of a luxury brand enthusiast. A prominently displayed name, however, unmistakably signals customisation to everyone.

Not all fear judgement

Importantly, we found not all luxury consumers share this fear of judgement equally. The impact depends on individual motivations for purchasing luxury items to begin with.

Those who are motivated to consume luxury goods for social reasons, such as standing out, are less concerned about receiving negative judgement from others.

In contrast, those who are motivated to buy luxury items for more individual reasons are more wary of how name personalisation might be judged.

For this group, which made up about half of the consumers we sampled, subtle, customised touches could be a more appealing option.

There could also be some variation across different cultures.

A report by KPMG found Chinese consumers – a group not included in our study – often seek luxury consumption as a means of social advancement and self-differentiation, meaning they are likely less concerned about the social costs.

On the other hand, we could speculate that Australian consumers, influenced by the “tall poppy syndrome” cultural phenomenon, may be even more sensitive.![]()

Anne-maree O'Rourke, Lecturer in Marketing, The University of Queensland