|

| President Trump is mistaken if he believes that tariffs will bring a new golden age of manufacturing. |

By James Scott, King's College London

The “liberation day” tariffs announced by US president Donald Trump have one thing in common – they are being applied to goods only. Trade in services between the US and its partners is not affected. This is the perfect example of Trump’s peculiar focus on trade in goods and, by extension, his nostalgic but outdated obsession with manufacturing.

The fallout from liberation day continues, with markets down around the world. The decision to apply tariffs on a country-by-country basis means that rules about where a product is deemed to come from are now of central importance.

The stakes for getting it wrong could be high. Trump has threatened that anyone seeking to avoid tariffs by shifting the supposed origin of a product to a country with lower rates could face a ten-year jail term.

The White House initially refused to specify how it came up with the tariff levels. But it appears that each country’s rate was arrived at by taking the US goods trade deficit with that country, dividing it by the value of that country’s goods exports to the US and then halving it, with 10% set as the minimum.

It has been noted that this is effectively the approach suggested by AI platforms like ChatGPT, Claude and Grok when asked how to create “an even playing field”.

Economically, Trump’s fixation on goods makes no sense. This view is not unique to the president (though he feels it unusually strongly). There is a broader fetishisation of manufacturing in many countries. One theory is that it is potentially ingrained in human thinking by pre-historic experiences of finding food, fuel and shelter dominating all other activities.

But for Trump, the thinking is likely related to a combination of nostalgia for a bygone (somewhat imagined) age of manufacturing, and concern over the loss of quality jobs that provide a solid standard of living for blue collar workers – a core part of his political base.

Nostalgia is not a sensible basis for forming economic policy. But the role emotions play in international affairs has been receiving more attention. It has been identified as an “emotional turn” (where the importance of emotion is recognised) in the discipline of international relations.

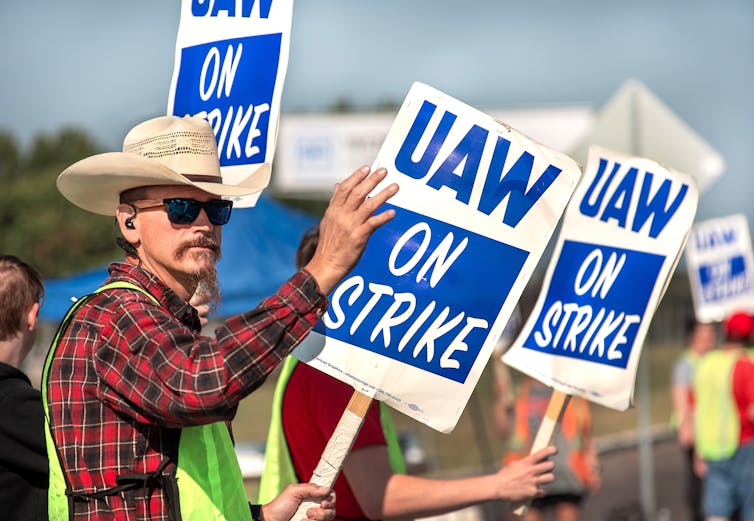

Of course, that’s not to say that the concern over jobs and the unequal effects of globalisation is misplaced. It is clear that blue-collar workers have suffered in the US (and elsewhere) for the last 40 to 50 years, with governments paying little attention to the decline.

Data on weekly earnings in the US split by educational level show that wages for those without a degree have declined or stagnated since around 1973, particularly among men. This is the cohort that disproportionately voted for Trump. Globalisation has created many benefits, not least to the United States, but these tend to be concentrated among the better educated.

All too often the service-sector jobs that have filled the gap left by declining manufacturing have been precarious. That means low wages, low security, lack of union representation and few opportunities for moving up the ladder. It is unsurprising that there has been a backlash.

Can’t turn back the clock

So will Trump’s tariffs plan address this? The great tragedy is that there is little reason to think that they will.

The loss of manufacturing jobs is partly about globalisation, which Trump is seeking to reverse. But research shows that trade and globalisation are often more of a scapegoat than a driving force, responsible for only a small chunk of job losses (typically said to be about 10%).

The main cause of manufacturing’s decline is rising productivity. Today it simply requires fewer people to make goods due to the relentless increase in automation and the associated rise in how much each worker produces.

If the whole US trade deficit were rebalanced through expanding domestic industries, this would increase the share of manufacturing employment within the US by about one percentage point, from about 8% today to 9% according to US Bureau of Labor Statistics figures. This is not going to be transformative.

The effects of tariffs are also doubled-edged. They will probably shift some manufacturing back to the US – but this could be self-defeating. More US steel production is good for workers, but the higher cost of US steel feeds through to higher prices for the products manufactured with it.

This includes the cars Trump obsesses about. Less competitive prices means lower exports and a loss of jobs. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away.

The 1950s were a unique time. By the end of the second world war, the US was a manufacturing powerhouse, accounting for one third of the world’s exports while taking only around a tenth of its imports.

There were few other industrialised countries at the time, and these had been flattened by the war. The US alone had avoided this, creating a world of massive demand for US exports since nowhere else had a significant manufacturing base. That was never going to last forever.

The other point about that time in history is that the economic system had been shaped by colonialism. European powers had used their position of power to prevent the rest of the world from industrialising. As those empires were dismantled and the shackles came off, those newly independent countries began their own processes of industrialisation.

As for the US today, President Trump is mistaken if he really believes that tariffs will bring a new golden age of manufacturing. The world has changed.![]()

James Scott, Reader in International Politics, King's College London