|

| La Place de Mougins in the heart of the village is also a highly regarded restaurant in this region famed for its gastronomy. Cover picture and photograph above by Andrea Heinsohn for DAM. |

Perched in the Provençal hills above Cannes, the village of Mougins

has quietly become one of the French Riviera’s most remarkable cultural

enclaves. Long favored by artists and intellectuals, this medieval town blends

centuries-old architecture with an unexpectedly modern artistic pulse. With

museums devoted to classical antiquities and contemporary women artists, a

culinary legacy shaped by world-class chefs, and panoramic views that once

inspired Picasso and Churchill alike, it offers a unique experience

for travellers seeking more than sun and sand along the Côte d’Azur, writes Jeanne-Marie Cilento. Photography by Andrea Heinsohn  |

Scents of lavender and rosemary fill the winding streets once home to artists Picasso and Picabia. |

ONLY a short drive from the cinematic dazzle of the French Riviera, the medieval

village of Mougins seems another world away: steeped in ancient history,

yet alive with the pulse of creativity. Here, amid the cypress and olive

groves, Picasso once sketched at twilight, Francis Picabia painted with surreal

abandon and Jean Cocteau wandered the spiraling lanes.

This sun-dappled commune in the French Alpes-Maritimes department is

more than just a picturesque village; it has a resonant artistic legacy and has been a place of cultural refuge that once welcomed and still opens its arms to artists, actors and writers. While its roots stretch back to pre-Roman times, it’s the

artistic migration of the 20th century that has etched Mougins into the global

cultural map.

In 1924, the avant-garde surrealist Francis Picabia was

among the first to fall under Mougins' spell. Drawn by the region’s light,

space, and tranquil remove from the bustle of Paris, Picabia set up home in the

old village, soon drawing an extraordinary constellation of friends and fellow

artists into his orbit. Fernand Léger, Paul Éluard, Isadora Duncan, Man Ray,

and Jean Cocteau were frequent visitors. Then came Pablo Picasso.

Amid the cypress and olive groves, Picasso once sketched at twilight, Francis Picabia painted with surreal abandon and Jean Cocteau wandered the spiraling lanes

|

The commanding sculpture of Pablo Picasso, commemorating his life and work in the town, |

From 1961 until 1973, Picasso lived just

outside the village at Notre-Dame-de-Vie, a simple farmhouse beside a

12th-century chapel that looks out over forests and valleys. His studio, now

the village’s tourist office, was a hub of activity and artistic output.

Neighbors still recall the way he moved quietly through the village, seeking

inspiration from the Provençal sun and the surrounding hills.

Today, a giant

sculpture commemorates his presence, but in truth, he never left, his spirit

inhabits every sun-bleached stone and winding alley. The allure of Mougins also drew stars from haute couture to the silver screen, from Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent to Edith Piaf and Catherine Deneuve, who all walked its cobbled lanes.

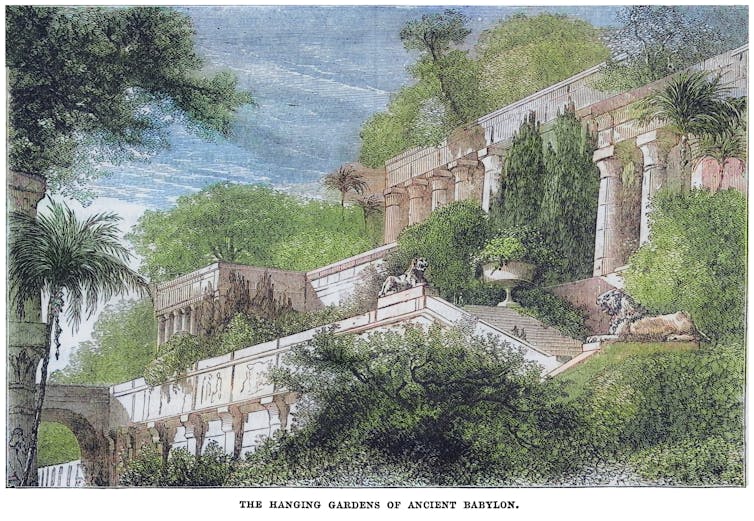

Mougins' connection to modern art is not merely anecdotal;

it is actively preserved and celebrated. The Mougins Museum of Classical Art

(MACM) stands as a cornerstone of this cultural identity. With more than 800

pieces spanning the ancient to the contemporary, Graeco-Roman sculptures

juxtaposed with works by Chagall, Matisse, Hirst, Cézanne, and of course,

Picasso and Picabia, it is a museum that challenges the boundaries

between epochs.

The allure of Mougins drew stars from haute couture to the silver screen, from Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent to Catherine Deneuve and Sean Connery

|

The FAMM museum housed in a traditional building, is devoted to women artists and is the first in Europe.

|

The museum is housed in a restored medieval building at the

edge of the old village. It is intimate yet rich, organized across four floors

that lead the visitor on a journey from Egyptian sarcophagi to neoclassical

sketches, culminating in modern and contemporary interpretations of the

classical form. The effect is to collapse time, allowing one to see the

dialogue between artists across millennia.

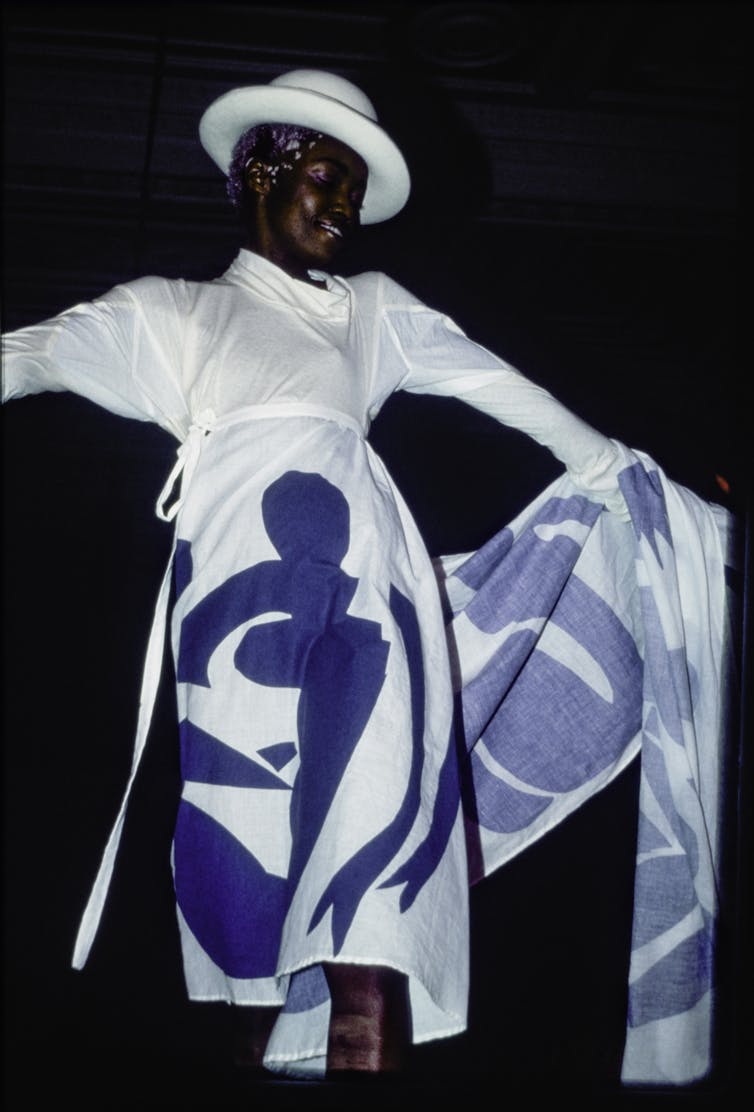

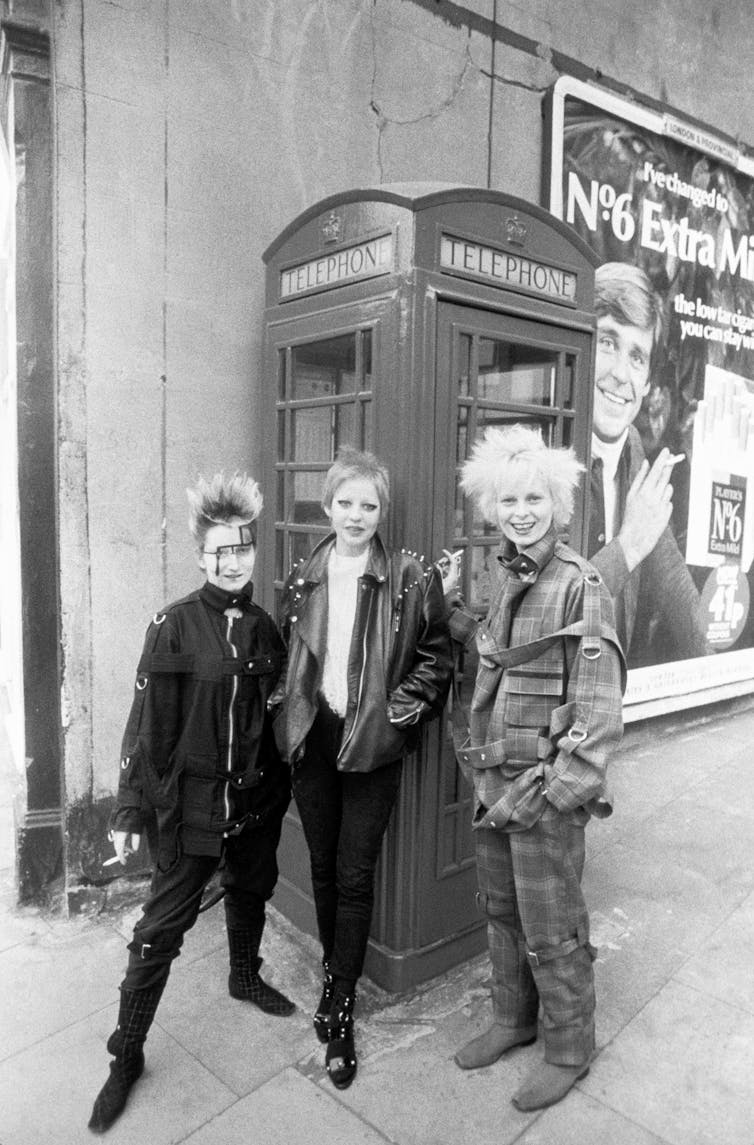

Mougins' artistic reinvention continues with the recent

opening of FAMM (Femme Artistes du Monde de Mougins) ~ a museum entirely

dedicated to the works of women artists. It’s the first of its kind in Europe

and already a major cultural landmark. Here, the canvases of Berthe Morisot

hang beside the bold self-portraits of Frida Kahlo and contemporary expressions

from Tracey Emin and Barbara Hepworth.

With its bright spaces and thoughtfully curated exhibitions,

FAMM serves as both a correction and celebration: a platform to reframe the

story of art through the eyes and voices of women who, like Picasso and

Picabia, sought freedom and inspiration in these hills. It’s a poignant

extension of Mougins' legacy as a creative refuge, now offering space for new

generations of visionaries.

The village's artistic reinvention continues with the opening of FAMM, a museum dedicated to the works of women artists and the first of its kind in Europe

|

Mougin's art scene is not only full of museums but also, private galleries and public installations. |

But the art of Mougins is not confined to its museums. It

spills out into the cobblestone streets, into its many private galleries and

public installations. Over 20 smaller art galleries are peppered throughout the

village, offering everything from abstract sculpture to Provençal landscapes,

all nestled within medieval architecture that adds an extra layer of charm.

And then there’s the Mougins Centre of Photography, set in a

restored presbytery in the heart of the old village. Its rotating exhibitions

highlight the evolving language of contemporary photography, presenting both

emerging voices and established names. Just as the MACM draws lines from past

to present, this centre ensures that Mougins remains deeply attuned to the

shifting pulse of modern visual culture.

Each summer, the village hosts Mougins Monumental, an

open-air exhibition of oversized sculptures installed throughout its plazas and

hidden corners. This collision of the monumental with the intimate offers

visitors a surprise around every corner, art not as something framed and

distant, but something to live among.

Mougins Centre of Photography, in a restored presbytery in the heart of the old village, has shows highlighting contemporary photography

|

Mougins has a lively gastronomic community of specialty shops and celebrated restaurants. |

If art is the soul of Mougins, then cuisine is its heart.

The village’s culinary reputation was established in the 20th century by Roger

Vergé, the charismatic chef who brought his “Cuisine du Soleil” to global

attention.

Light, fresh, and rooted in Mediterranean tradition, Vergé’s cooking

redefined French gastronomy. His Michelin-starred restaurants, L’Amandier and Le

Moulin de Mougins, attracted a star-studded clientele, from Elizabeth Taylor to Sharon Stone.

Vergé’s influence still flavours the village. L’Amandier

remains a landmark, housed in a building that once served as the medieval

courthouse for the monks of Saint-Honorat. Today, its windows open to views of

pine forests and tiled rooftops, while the kitchen serves dishes that celebrate

local ingredients with sun-drenched simplicity. Alain Ducasse, another titan of

French cuisine, honed his craft under Vergé here in the 1970s.

If art is the soul of Mougins, then cuisine is its heart. The village’s culinary reputation was established in the 20th century by Roger Vergé,

|

To celebrate its culinary history, the town holds a bi-annual festival that brings the world's greatest chefs together. |

In honor of this culinary heritage, Mougins created Les

Étoiles de Mougins, an international gastronomy festival first held in 2006.

The festival brings together world-class chefs for demonstrations, tastings,

and debates, turning the entire village into an open-air kitchen every two years.

Since 2012, Mougins has held the exclusive title of “Ville et Métier d’Art” for

gastronomy, a distinction no other French town shares.

While art and food may draw most modern visitors, the stones

of Mougins carry the weight of centuries. From its early days as a Ligurian settlement to its medieval

fortifications, the village has borne witness to empire and invasion. The town's roots run deep, archaeological finds indicate that

the site was first occupied by Ligurian tribes long before the rise of the

Roman Empire.

Over the centuries, the elevated, spiral-shaped design proved a strategic advantage, built to withstand invasion, the medieval village was enclosed by ramparts with three main gates

|

The soaring 18th century bell-tower of the Saint Jaques-le-Majeur church |

The Romans eventually established a settlement called Muginum

along the ancient Via Aurelia, the road that once connected Rome to Arles. In

the 11th century, the land was handed over to the monks of Saint Honorat, who

governed the area from the island monastery just off Cannes. The vestiges of

this monastic influence remain visible today in the village’s architecture, particularly

in the vaulted “Salle des Moines,” now part of a renowned restaurant.

Over the centuries, Mougins’ elevated, spiral-shaped design

proved a strategic advantage. Built to withstand invasion, the medieval village

was enclosed by ramparts and accessed through three main gates, only one of

which, the Porte Sarrazine, remains today.

Though attacked and partially

destroyed during the War of the Austrian Succession, Mougins gradually rebuilt,

maintaining much of its circular medieval charm even as new streets were added

in the 19th century.

A walk through the village reveals these architectural layers of

this history. The Porte Sarrazine still stands as the sentinel of the old spiral-shaped fortress. The

narrow streets echo with footsteps from every century, from monks who

administered the town for the Abbey of Saint-Honorat to Napoleon himself, who

passed through Mougins on his march north from Elba in 1815.

A plaque marks the modest house where Commandant

Amédée-François Lamy, the French military figure who would give his name to the

Chadian capital (now N’Djamena), was born in 1858. It is one of many small

historical markers that lend the village its living yet historic character.

For those who venture beyond the bright lights of Cannes, Mougins offers something rare: a village where art, history, nature, and flavor converge in harmony

|

The pool of La Réserve by Mougins Luxury Retreats, which has accommodations throughout the village.

|

Mougins' hilltop location isn’t just strategic; it’s

spectacular. The view over the Alps is uninterrupted and

breathtaking. In the golden light of the late afternoon, the rooftops glow and

the valleys turn to velvet.

It’s easy to see why Winston Churchill, a neighbor

of Picasso’s, chose to write and paint here, often seated near the chapel of

Notre-Dame-de-Vie, where silence reigns and olive trees sway like gentle muses.

Although there is a sense of quiet luxury ~ boutique hotels and curated shops now fill restored buildings ~ the village retains its

spirit. It isn’t flashy or overrun. It welcomes, rather than dazzles. It charms

rather than overwhelms.

For those who venture beyond the bright lights of Cannes,

Mougins offers something rare: a village where art, history, nature, and flavor

converge in harmony.

It is a place where Picasso painted and dined, where

Picabia laughed with friends, where sculptures rise from cobbles and perfumes scent the air from pressed flowers. It is a reminder that the Riviera’s soul lies

not on the beach, but in the hills above. And in Mougins, that soul still whispers ~ through a shuttered

window, from behind a canvas, across a sunlit terrace.

|

A pretty doorway with a solid walnut door and stone steps. |

Getting There: Mougins is a 15-minute drive from Cannes. The

nearest airport is Nice Côte d’Azur, approximately 30 minutes by car.When to Go: Spring and early autumn are ideal, with warm

days and fewer tourists. Visit in June for the Gastronomy Festival or in summer

for art events and music festivals.

Don’t Miss:

The Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins (MACM)

The FAMM Museum of Women Artists

A meal at L’Amandier

Sunset at Notre-Dame-de-Vie

Climbing the belltower of the Saint Jaques-le-Majeur church for the spectacular view across Provence to the sea,

Tip: Take your time. Mougins isn’t a place to rush. It’s

a place to wander, to linger, to let the village reveal itself, one spiral

street, one delicious bite, one quiet moment at a time.

![]()