Photography is almost 200 years old and Photography: Real and Imagined at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) can be interpreted as an attempt to make sense of its history.

A huge and dazzling exhibition containing 311 photographs, the basic thesis of this exhibition is that some photographs record an actuality, others are purely a product of the photographer’s imagination, while many are a mixture of the two.

The parameters of the exhibition are determined, in part, by the holdings of the NGV collection and, in part, by the perspective adopted by the curator, the erudite and long-serving senior curator of photography at the NGV, Susan Van Wyk.

Mercifully, the curator has not opted for a linear chronological approach from daguerreotypes to digital, although both are included in the exhibition, but has devised 21 diverse thematic categories, for example light, environment, death, conflict, work, play and consumption.

Australian artists, international context

The categories have porous boundaries. Even with the assistance of the 420-page book catalogue, it is difficult to determine why Michael Riley’s profoundly moving photograph of a dead galah shown against the cracked earth belongs to the environment theme instead of death; why Rosemary Laing’s Welcome to Australia image of a detention camp belongs to movement, instead of being in community, conflict or narrative.

I felt that there was a perceived need to somehow organise the material, and the broad thematic structure allows the viewer to develop some sort of mega-narrative for the show.

There is also evident a desire to create an international context within which to display the work of Australian photographers.

It is indeed a very rich cross-section of Australian photographers assembled in this exhibition. This is not an Anglo-American construct of the history of photography; Australian photographers are presented together with New Zealanders and their Asian contemporaries.

Although the NGV boasts of having the first curatorial department of photography in any gallery in Australia, in the department’s 55-year history there remain serious lacunae in the collection.

For example, Russian constructivist photographers, including Aleksandr Rodchenko, who, as far as I am aware, in the NGV collection is represented by a single small booklet, but looms large in any account of the history of photography as presented by the British, European and American museums. Eastern European photographers are also generally underrepresented.

Key moments, and surprises

This exhibition combines the iconic with the new and the unexpected.

The expected key moments in the history of photography are generally all present with the roll-call of names including Dora Maar, Man Ray, André Kertész, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Dorothea Lange, Eadweard Muybridge, Bill Brandt, Lee Miller and László Moholy-Nagy.

They are all included in the exhibition and are represented through their iconic pieces.

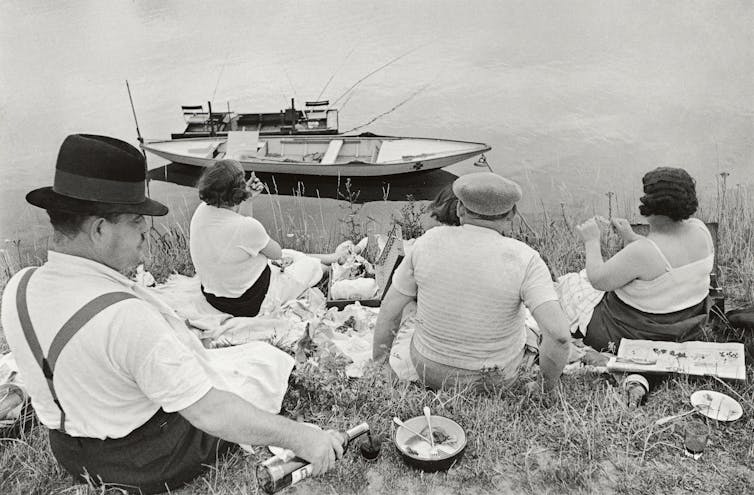

Henri Cartier Bresson’s Juvisy (1938), colloquially known as Sunday on the banks of the Marne, is an intentionally subversive image by this left-wing radical photographer.

This image, made at the height of the Great Depression, shows a victory by France’s popular left-wing government that legislated in 1936 the entitlement for French workers to have two weeks of paid vacation. Here the working class is enjoying a picnic at Juvisy, just to the south of Paris.

At about the same time, Dorothea Lange’s Towards Los Angeles, California (1936) contrasts the anguish of the unemployed trekking in search of work and a billboard advertising the comforts of train travel. An aphorism ascribed to her sums us much of her work:

Bad as it is, the world is potentially full of good photographs. But to be good, photographs have to be full of the world.

Man Ray’s Kiki with African mask (1926) is one of the most famous photographs in the world, also known as Noire et blanche (Black and White). The surrealist artist juxtaposes the elongated face of his Muse and mistress, Kiki (Alice Prin), with her eyes closed with that of a black African ceremonial mask.

The photograph was controversial when it was first published and continues to be controversial to the present day.

There are also numerous modern classics in the exhibition, including Pat Brassington’s Rosa (2014), Polly Borlan’s Untitled (2018), from MORPH series 2018 and Robyn Stacey’s Nothing to see here (2019), that can all be viewed as edging into the realm of the uncanny. Beyond the façade of the familiar, we are invited to enter an unexpected world.

Reinterpreting our world

Photography’s reputation of creating a trustworthy facsimile of the real had long been eroded, even before the creation of digital software. There is an old adage, “paintings sometimes deceive, but photographs always lie” – precisely because there was a perception that they could not lie.

One of the most intriguing works in the exhibition is by the New Zealand-born photographer Patrick Pound, titled Pictures of people who look dead, but (probably) aren’t (2011–14). It is a sprawling installation of mainly found photographs where the audience is invited to create a life and death narrative.

Photography: Real and Imagined reexamines our thinking about the art of photography and explores photography’s ability to recreate and reinterpret our world.

Photography: Real and Imagined is at the Ian Potter Centre, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, until February 4 2024.![]()

Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.