Monday, 18 September 2023

Tuesday, 12 September 2023

Kate Barton is Redefining American Eveningwear with Innovation and Sustainability

|

| Kate Barton's shimmering new SS24 collection with its gleaming accessories and innovative materials, presented in New York. Cover picture by Anna Nguyen |

One of the highlights of New York Fashion Week was the new Spring/Summer 2024 collection by American designer Kate Barton. Her unique blend of innovation, technology, avant-garde draping, and shape engineering has made her sleekly futuristic designs a standout, writes Isabella Lancellotti

|

Glimmering and gossamer-fine, the American designer's take on modern eveningwear |

Barton embraces a fabric-first philosophy that optimizes volume without resorting to unnecessary layering, resulting in a modern classicism that is both elegant and innovative.

What makes Barton's creations exemplary are her materials and craftsmanship. The Spring/Summer 2024 collection features chrome leather accessories and magnetized detachable enhancements, creating the illusion of metal while still ensuring practical wearability.

The introduction of crystal-encrusted sculptural belts adds a touch of opulence and whimsy, seamlessly blending sustainability, creativity, and unapologetic luxury. The designer wants to create a couture aesthetic with inventive sculptural garments, engineered materials, sustainable technology-driven cutting, and fabric manipulation.

What makes Kate Barton's creations exemplary are her fresh ideas, experiments with unusual materials and fine craftsmanship

|

Exquisite draping and new materials make Barton's work a standout. |

During the pandemic, she had limited access to machinery and materials, which drove her to try out unusual materials and sustainable methods.

The designer wants to redefine eveningwear but also advocates for positive change. Her profile has grown inside and outside the fashion world as she gains recognition from her peers and the high-profile women she has designed gowns for, from Heidi Klum and Kat Graham to Paige DeSorbo, and Wallis Day.

Kate Barton's vision for the future of American eveningwear is clear. She is eager to continue explore the nature of luxury fashion, bringing a modern approach not often seen in this sector.

Her approach is refined each collection, as she evinces how new technology and materials can be utilized without compromising on style and luxury.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Monday, 11 September 2023

New York Fashion Week: AREA'S Ready-to-Wear and Couture AW23 Collection

|

| The clever trompe l'oeil fabric made to look like luxurious fur, created by AREA, as part of their new collection, shown at New York Fashion Week. Photographs courtesy of Arena |

|

It looks like fur but is a trompe l'oeil version created by Area |

|

Resin bones encrusted with crystals become part of the fur-printed gown |

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Tuesday, 5 September 2023

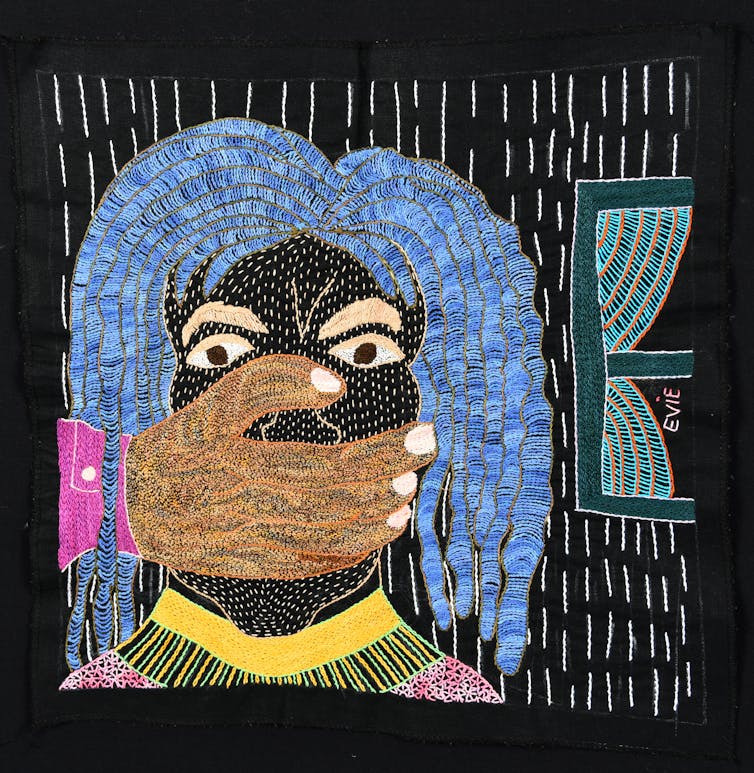

The power of Needlework: How Embroidery is Helping South African Women Tell Their Stories

|

| In her artwork for the project, Christine Leputla depicted victims of domestic violence fleeing their attacker |

By Puleng Segalo, University of South Africa

In June 2020, three months after South Africa entered the first of a series of hard lockdowns to slow the spread of COVID, the country’s president Cyril Ramaphosa described men’s violence against women as a “second pandemic”.

In the first three weeks of that lockdown the Gender Based Violence Command Centre, designed to support victims of gender-based violence (GBV), recorded more than 120,000 victims. Also in its 2019/2020 crimes statistics, the South African Police Services indicated that an average of 116 rape cases were reported each day.

While South Africa’s GBV crisis is not new, it was exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, which made the perpetual challenges faced by many women and gender non-conforming individuals hyper visible.

This visibility sheds light on the reality that the home is a complex space where care and violence can co-exist. Women can feel simultaneously safe and in danger in their homes. All of this happens behind closed doors, often robbing women of a voice to express their fear, suffering and pain.

That affects more than just individual women: GBV is a collective, structural challenge. When women are violated at homes, it affects familial relations, productivity at work, and overall societal functioning.

I am a psychologist who wanted to harness the power of visual artistic expression to highlight the multi-layered ways in which gendered violence is woven into everyday encounters. To do so, I turned – as I have done in previous research – to embroidery.

As I have written in my previous research into the role of embroidery in empowering women’s storytelling, for this current work, I drew again from this methodology to visually tell the narrative of GBV in colourful and creative ways, paying attention to moments of encounters where those who perpetrate and those against whom the violence is perpetrated appear in the same frame. The visual artwork invites the viewer to witness. The hope is that beyond the witnessing is a call for action.

Everyday violence

Beyond making visually appealing artwork, needlework has always been a useful tool to tell difficult or unspeakable stories. Through depicting their lived experiences of gender trauma, women can have an outlet for their pain. While their embroideries serve as a canvas for the outpouring of pain, loss and trauma, their work also tells stories of hope, resilience and resistance.

For this research I worked with the Intuthuko women’s collective. The group consists of 16 Black women based in one of the townships (these are historically Black urban residential areas) in Ekurhuleni in the Gauteng province. GBV in South Africa continues to affect Black women disproportionately, a reality rooted in history as well as in present systems.

The idea with this project was to let the visuals do the talking. So we did not focus on personal experiences, but an overview of the many ways in which GBV shows itself in our lives. I was part of the group and also contributed in making an embroidery piece. This allowed me to shift from being just a researcher and spectator to becoming a contributor in the process of thinking, reflecting and making. It was a collaborative endeavour where we came up with themes as a collective and then each focused on a particular theme for the making of the embroideries.

During the process of making the embroideries, we would share stories of how GBV constantly affects our communities, reflecting on the need to use these embroideries as a form of awareness raising, tool for community dialogues, and to challenge the patriarchal system that has rendered the world unsafe for women.

The aim was to highlight the multi-layered ways in which gendered violence is woven into everyday encounters. We sought to engage the ways in which creative meaning could be made of GBV in our communities – and how the challenges facing our society because of gendered violence could be given attention.

Perpetual fear

The embroideries depict a society where fear is manufactured, created, and produced by patriarchal and unjust structural violent systems. This in turn leads to women living in perpetual fear; they cannot feel safe within and outside of their homes.

Through our artistic visual depictions, we expressed how GBV creates a sense of women being regulated and controlled, and of not entirely owning their bodies.

Some embroideries featured women being violated and robbed in public places, reduced to kneeling down for mercy. The artworks highlighted women’s sense that the streets are not safe and that they are never sure whether they will make it back home safely.

Feeling unsafe and in a constant state of fear makes it difficult for many women to exercise their agency: when society is structured in ways that make women victims, patriarchy prevails.

Staring reality in the face

These embroideries are not just pieces of visual art. They are a challenge to the viewer to stare the violence in the face with the hope that they will be compelled to reflect and to act.

The embroideries have been displayed at an art exhibition where the public could attend and engage with the pieces. We also produced a multilingual visual booklet which is being used in the women’s community and schools as a tool for opening up dialogues on GBV.![]()

Puleng Segalo, Chief Albert Luthuli Research Chair, University of South Africa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Monday, 28 August 2023

Travel: Champagne is Deeply French ~ but the English Invented the Bubbles

|

| Shutterstock |

In 1889, the Syndicat du Commerce des Vins de Champagne produced a pamphlet promoting champagne at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, claiming that Dom Pérignon, procurator of the Benedictine Abbey of Hautvillers from 1668, was the “inventor”, “creator” or discoverer" of sparkling champagne.

“Come, Brothers! I drink stars!” is the famous quote often attributed to him.

The story of a blind monk having an epiphany, accidentally happening upon the secret to effervescence, was seductive. It combined divine revelation and French winemaking expertise to produce a national symbol deeply rooted in the French landscape.

However, the truth is slightly different. Dom Pérignon did contribute to improving the still wines of the Champagne region, but he did not discover effervescence – he was trying to get rid of the bubbles.

The champagne myth

The expo where the champagne myth was propagated marked the 100-year anniversary of Bastille Day and is best known for the debut of another icon of French culture, the Eiffel Tower. The Pérignon story gained traction at the same moment these other symbols of nation-building reinforced the uniqueness of French culture and history.

The basis for the myth can be traced to a letter from Dom Grossard of Hautvillers Abbey to the mayor of Aÿ, in the heart of the Champagne region. Grossard claimed that Pérignon had perfected the method for making perfectly white wine from pinot noir grapes (blanc de noirs), pioneered the technique for effervescence, and championed the use of bottles and corks.

Only the first of these claims is true. At the abbey, wooden stoppers and canvas soaked in grease were used to seal bottles, and French glass was too weak to contain the pressure from effervescence. A bigger problem was that French winemakers – and consumers – considered bubbles a fault, a trick to distract the drinker from bad wine.

Prominent French wine merchant Bertin de Rocheret advised a client who inquired about sparkling wine:

effervescence obscures the best characteristics of good wines, in the same way that it improves wines of lesser quality.

Bubbles, bottles and corks

The method for effervescence, strong glass bottles and the use of corks all came from England in the 17th century. English consumers imported wine in barrels from France because bottles were taxed at a higher rate than wine imported in bulk.

The wines often deteriorated during the journey across the channel and once opened, they oxidised quickly, developing an unpleasant flavour. To improve the taste, consumers added honey, syrup made from raisins or sugar. The additional sugar content caused a secondary fermentation – and effervescence.

In 1662, Christopher Merrett, a founder of the Royal Society, published a paper titled “Some Observations Concerning the Ordering of Wines”, in which he described the method for effervescence:

Our winecoopers of latter times use vast quantities of sugar and molasses to all sorts of wines, to make them drink brisk and sparkling, and to give them spirits, as also to mend their bad tastes.

To produce sparkling wine and retain the effervescence, three things are necessary: bubbles, strong glass bottles and corks.

Merrett’s method provided the fizz, and corks were already used in England for bottling cider and perry. Strong glass in England was a by-product of a prohibition on using wood in industrial furnaces, decreed by King James I in 1615.

Timber was too valuable to be burned for glassmaking, reserved for building ships for the merchant fleet. Using sea coal, English glass furnaces reached higher temperatures and produced stronger glass. These bottles could withstand pressure (as much as a car tyre) without bursting.

The paradox?

The only ingredient the English lacked was wine, prompting French wine historians to refer to their contribution as “The English Paradox”. How could a country with no winemaking tradition pioneer the technique for effervescence? The “paradox” label, however, only makes sense if the traditions and standards of French winemaking are presumed to be superior.

Bound by tradition, French winemakers were unwilling to contemplate a fault as a desirable innovation. Driven by necessity, and without any winemaking rules, English consumers were free to experiment.

But necessity was only part of the equation – English culture did play a part in the success of effervesce. Reserving timber for the English fleet made for stronger glass, and cider and perry production provided corks to seal the bottles.

The French champagne industry now claims effervescence was not invented, but is a natural product of the soil and climate in a strictly defined region.

Natural fermentation does produce some fizz, but rarely enough to pop a cork without the intervention of a winemaker. The emphasis on nature reinforces the exclusivity and unique geographic attributes to distinguish champagne from all other sparkling wines.

A more complex history of the origin of effervescence challenges preconceptions about national identity, even in matters of taste. This does not diminish champagne’s luxury status, but it does reveal the influence of cultural traditions on innovation, and the many influences that pave the way to novelty.![]()

Garritt C Van Dyk, Lecturer, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Tuesday, 22 August 2023

Interested, Curious and Empathetic, Michael Parkinson Helped Bridge the Gap Between Australia and England

|

| AAPImage/Network Ten |

By Lea Redfern, University of Sydney

Michael Parkinson demonstrated the art of the good interview night after night. He practised deep listening, giving his interviewee his full attention, but he was always aware of the audience. While he was asking questions on behalf of the audience and advocating for the audience, he always had the person he was interviewing as his focus.

As host of Parkinson (1971–82 and 1998–2007) and Parkinson in Australia (1979–83), he was a big presence on Australian TV. He was television the whole family could watch together, never unsuitable for children.

We may not have understood everything, and some references went over our head, but as children we could watch Parkinson with our parents. I remember as a young person regularly watching him and hoping the interview would be funny that week.

There were times you knew it was going to be hilarious. When Billy Connolly or “our” Dame Edna were going to appear it was a must-watch.

Whoever the interviewee, Parkinson brought out their stories, their observations. He gave them space to share engaging stories and never stepped on a punchline. Although humour was a draw card for the audience, there was space for pathos, too.

Finding the shape

Parkinson was an interviewer of great skill. He could be a presence, but never pull focus from the interviewee. He was deeply empathetic, and always in control of the interview.

The form of the interview was always satisfying: he knew how to draw a narrative through the length of the program. When interviewing three people at once, he knew how to be fair and have a balance between everyone and their stories. He made this appear effortless.

From 1979 to 2014 he frequently worked in Australia across the ABC, Channel Ten and Channel Nine.

For a generation of ten pound passage immigrants, he represented the best of the old country: he was never patronising, never spoke down to people, and helped to bridge the gap between Australia and England. He was able to bring us the best of British and Australian interviewees alike, affirming Australia’s international standing in the arts and culture.

When speaking to Australian politicians, sports stars and actors he was always deeply interested and deeply curious. He could reflect us back to ourselves without any of the cultural cringe so evident in the media of the time. The affection Australians felt for him is shown in the diminutive “Parky”.

An authentic voice

Born in Yorkshire in 1935, Parkinson didn’t attend university, starting his career working for newspapers straight out of school. It was perhaps this start which aided in his plain speaking common sense and ability to talk to ordinary people. You got the sense he could speak to anybody. There was no putting on a persona; he was always authentically him.

Today, this authentic self is seen in many of our best interviewers. We know how important it is curiosity and authenticity drive the interview – Parkinson was doing this decades before others recognised its importance.

When I started in radio, I looked towards Parkinson as the gold standard. I admired how he was able to draw people out and reveal so much of themselves. He demonstrated how the media could go beyond the soundbite.

So much of the media of the time was about context-free news and current affairs journalism. Although his interviews were with celebrities, he showed people might share more of themselves and the world if they’re given time and space to speak. Parkinson gave us a fuller, richer sense of the people he spoke to.

His legacy in Australia can be seen in people like Andrew Denton, Richard Fidler and Sarah Kanowski – long form interviews driven by curiosity.

Some people have been describing Parkinson’s death as the end of an era, but his legacy will live on. When we look at shows like ABC Conversations, and so many longform podcasts, we find curious interviewers who, like Parkinson, build a relationship and find a connection with an interviewee. A soundbite might show up on TikTok or YouTube – but you have to do the longform interview to get there.

Perhaps one of the best demonstrations of this was Parkinson’s interview with Ian Thorpe. In the 2014 interview, Thorpe came out publicly for the first time, and spoke about his depression and use of drugs and alcohol.

Without the relationship Parkinson was able to build over the course of the interview, it is doubtful Thorpe would have felt comfortable to come out in the same way. Parkinson was always interested in giving people the opportunity to reveal themselves.

That Thorpe felt Parkinson’s show was a safe space to come out says something about the tenor of his relationship with his interviewees and his place in Australian culture.

There for the audience

His few missteps seemed to be with women. As I grew older, I realised he was a man of his time, as was made obvious in his awkward interviews with Meg Ryan and Helen Mirren. In these interviews, his occasional awkwardness around gender is writ large, and the interviews go off the rails. He fails to develop his famous rapport and adjust his approach in response to their discomfort.

But given the length of his career, the rarity of these missteps is still impressive. His geniality and quiet generosity came across night after night, for decades.

What defined him more than anything was how he was inclusive of his audience. No matter how complex the ideas or how smart the person he was interviewing, the audience was brought along with them. He was there on our behalf, and able to ask the clarifying questions without worrying about his own ego.

He represents an age of Australian and British relationships in a way that is truly singular and his interviews are artefacts of that age. He was an interiewer who stood out for not having to stand out, and the delights and possibilities of the long-form interview are his legacy.![]()

Lea Redfern, Lecturer, Discipline of Media and Communications, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Tuesday, 8 August 2023

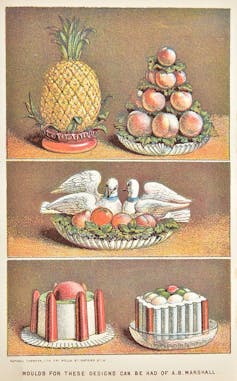

Travel: The Strange History of Ice Cream Flavours – from Brown Bread to Parmesan and Paté

|

| Noblewomen eating ice-cream in a French caricature, (1801). Gallica |

English Heritage is now selling what it calls “the best thing since sliced bread” at 13 of its sites ~ brown bread ice cream, inspired by a Georgian recipe. The announcement of the flavour mentions several more outlandish Georgian flavours trialled by English Heritage before it landed on brown bread, such as Parmesan and cucumber.

English Heritage is not alone in its efforts to beguile visitors with historical treats. In Edinburgh, the National Trust for Scotland’s Gladstone’s Land features an ice cream parlour linked to the dairy which stood there in 1904. The property sells elderflower and lemon curd ice cream based on a recipe from 1770, and visitors can go on several food-themed tours.

While brown bread ice cream, praised for its caramel nuttiness, may be a more familiar flavour to contemporary eaters than other historical offerings, the iced delights eaten in Britain in previous centuries took a huge variety of flavours and forms.

Agnes Marshall, the authority on ice cream during the late 19th century, published two cookbooks specifically about “ices” (1885) and “fancy ices” (1894). They included flavours from an elaborately moulded and coloured iced spinach à la crème, to little devilled ices in cups.

The latter consisted of a chicken pâté spiked with curry powder and Worcestershire sauce, egg yolks and anchovies, which was then mixed with gravy, gelatine and whipped cream, before being frozen in decorative cups and served “for a luncheon or second-course dish”.

Earlier texts contain even more outlandish flavours alongside the typical, sweet offerings.

French foodie Monsieur Emy’s L’Art de Bien Faire les Glaces d’Office (1768) has recipes for truffle, saffron and various cheese-flavoured ice creams.

The history of ice cream

By the time Marshall was publishing, ice cream was far more accessible to the public than in earlier centuries. Prior to the 1800s, ice was collected from frozen waterways and stored in underground ice houses, largely restricted to large estates with the necessary land, wealth and resources.

From the 1820s, however, ice was imported to Britain from Europe and then the US and stored in ice wells and warehouses. The importation of larger stocks of ice reduced costs, while simultaneously, innovators were designing apparatus for mechanical freezing.

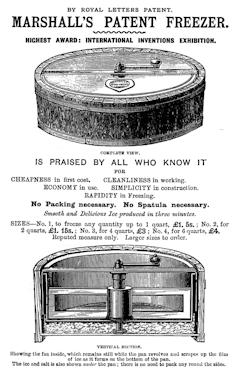

It would be a long time until ice was easily produced within the home, but cheaper ice made ice cream more readily available and implements were devised so it could be made at home. Both Emy and Marshall’s cookbooks depicting ice cream makers and Marshall’s patent freezer enlisted the same freezing technique as Emy’s Sarbotiere et son Seau (pot freezer and bucket).

Ice and salt were placed around a bucket, within which a custard or water mixture was stirred or rotated until it froze. Marshall’s innovation was the shallow pan, which gave an increased surface area for faster freezing. Equipped with such a freezer (and perhaps Marshall’s patent Ice Cave, for storing the ices), middle-class housewives could produce ice cream in their own kitchens.

Ice cream and leisure

Ice cream is well suited for engaging visitors at heritage properties today, not because of the history of how it was produced within the home but because of its holiday connotations. Whether it is a “99”, an “oyster” enjoyed at the beach, or the nearing jingle of an ice cream truck, ice cream has clear cultural and emotional links to recreation and enjoyment. This was also true in the past.

In 19th century Britain, street vendors (many of them Italian immigrants) began selling penny licks, or “hokey-pokey” from stalls or carts in the streets. In contrast to the immaculately-moulded delicacies in Marshall’s cookbook – which required the purchase of several pieces of equipment – this ice cream was to be enjoyed while out and about. It was also cheap, as implied by “penny” in the title.

Customers would purchase their ice upon a glass “lick”, eat it and then return the lick to the vendor for reuse. With growing numbers of seaside resorts and the rise of the leisure industry over the 19th century, ices were enjoyed while on holiday or daily excursions and at public events like exhibitions or fairs.

It is the portability of ice cream, as well as its culinary appeal, that has led to its lasting place in our leisure time – a delicious treat that can be enjoyed, one-handed, as part of a larger experience. The act of eating ice cream prepared from a Georgian or Victorian recipe therefore connects today’s visitors to a long tradition of enjoying ices recreationally.

While heritage properties are unlikely to embrace the more unsanitary ways ice cream used to be eaten, serving up historical recipes gives visitors a chance to savour a new sensory layer of the past. That taste can be linked into larger histories. From ice cream, we can learn about technological developments, changing attitudes towards sanitation, global travel, the availability of ingredients throughout time, trends, fashion and leisure habits.

Delving into the history of food – from the tins in our cupboards, to a cup of tea, or an ice cream at the beach – can bring new perspective to both the past and the present.

Lindsay Middleton, Food Historian and Knowledge Exchange Associate, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.