When you think about a red object, you might picture a red carpet, or the massive ruby in the Queen’s crown. Indeed, Western monarchies and marketing from brands such as Christian Louboutin have cemented our association of the colour red with power and wealth.

But what if I told you this connection has been pervasive across time and cultures? In fact, the red pigment has fascinated humans for millennia.

Prickly pear blood

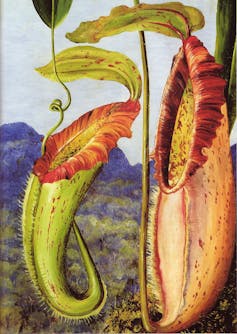

The vibrant red we often see in cosmetics, food and drinks is actually derived from a tiny insect called the cochineal, which lives on prickly pear cacti and today is harvested mainly from Peru and the Canary Islands. The cochineal’s ubiquitous crimson dye is also known as Carmine, Natural Red or E120.

The links between red and esteem and power can be traced back to the Inca civilisation that flourished in the Andean region of South America from around 1400 to 1533.

Red carries profound symbolism in Inca mythology, intertwined with the legendary story of Mama Huaco – the inaugural warrior queen – who was often envisioned as emerging in a resplendent red dress.

The historical journey of the cochineal mirrors the journeys of several other global staples – such as potatoes, chilli and tomatoes – that originated from pre-Columbian Mexico and South America.

The cochineal insect was brought to Europe by Spanish conquistadors in the 15th century, and held a worth akin to gold and silver. It strengthened Spain’s economic influence, provided support for the Spanish empire’s expansion, and stimulated global trade.

Cultivation and harvest were carried out by the Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples living under Spanish rule, who had already been doing this for centuries. They were paid in pennies while their labour allowed Spain to maintain its monopoly on the valuable red dye.

The king’s shoes

Before the conquistadors began the cochineal trade, achieving a rich red hue was a challenge, which meant European nobility had to use purple and blue instead.

But by the 1460s, the cochineal gained such popularity in Europe that it superseded Tyrian purple as the traditional colour of the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church. This red was unmatched in vibrancy. Its depth and rarity eventually made it among the most expensive dyes of the time.

It became a prominent feature in European Baroque art – characterised by its intensity and drama. And its widespread uptake by European royalty further solidified its connection with power and wealth.

In France, King Louis XIV’s (1638-1715) penchant for red was evident in his lavish décor choices, which included 435 red beds in his palace at Versailles. He displayed red in the soles of his shoes. He even instituted a law in 1673 restricting the coveted red heels to aristocrats who were granted permission by the monarch himself, effectively making them a hallmark of royal favour.

Spiritual significance

The colour red holds significant spiritual symbolism across various religions. In Judeo-Christian traditions, an intriguing connection exists between the Hebrew word for “man” (Adam), “red” and “blood”, all stemming from a common etymological root.

According to Biblical accounts, Adam, the first man, was formed from the Earth – and the colour red could symbolise the richness of the soil or clay from which Adam was created. This interplay of language and symbolism underscores a profound interconnectedness between red and spiritual belief systems.

This spiritual significance reverberates across cultures. In Hindu tradition, red is imbued with sacred meaning symbolising fertility, purity and prosperity. In Chinese culture, it is considered auspicious, and signifies joy and prosperity.

Red hues have also been viewed as a symbol of vitality across spiritual and cultural groups, as they emulate blood, our life force. In Roman Catholic tradition, red is symbolic of martyrdom, the spirit and the blood of Christ.

The colour of champions

In terms of visibility, red has the longest wavelength. This might help explain our longstanding cross-cultural attraction to it: studies show it stimulates excitement and energy when viewed, which can cause physical effects such as an increased heart rate. It has even been shown to increase our appetite.

Psychologically, red seems to have more influence on humans compared with other colours in the spectrum. In an experiment at the 2004 Athens Olympics, athletes across four contact sports were randomly clad in either red or blue. Those who wore red were more often victorious.

Another study of English football teams over a 55-year period found wearing red shirts was associated with greater success on the field. That’s because red is linked to a heightened sense of determination and endurance, which can translate to better focus. From this angle, red seems to be the colour of champions.

The “red carpet” tradition itself is thousands of years old. The first known reference to it comes from the ancient Greek play Agamemnon, written in 458 BCE, in which a red path (said to be reserved for the gods) is laid out for King Agamemnon by his wife as he returns from the Trojan war. The twist is that Clytemnestra seeks to lead him to his death:

Let all the ground be red / Where those feet pass; and Justice, dark of yore, / Home light him to the hearth he looks not for.

This symbol has since morphed into the celebrity red carpet, graced by pop culture “royalty”.

Meanwhile, red also has also garnered some alarming associations in our everyday vernacular, with “red pills”, “red flags” and “seeing red” being just a few examples.

This potent symbol continues to have diverse interpretations, representing not only achievement, but also the power – and sometimes the dangers – that come with it.![]()

Panizza Allmark, Professor Visual & Cultural Studies, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.