Wednesday, 18 January 2023

Tuesday, 17 January 2023

Monday, 16 January 2023

Friday, 6 January 2023

New Exhibition: Behind-the-Scenes of Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio Film at the Museum of Modern Art in New York

.jpg) |

| Film director Guillermo del Toro with a puppet of villain Count Volpe on the set of Pinocchio. Image courtesy Jason Schmidt/Netflix |

|

The director gazes at a Pinocchio puppet with the spectacular church set in the background. Image courtesy of Jason Schmidt/Netflix |

.jpg) |

Co-director Mark Gustafson with Guillermo del Toro on the set of Pinocchio. Image courtesy of Jason Schmidt/Netflix |

|

Sets from the film showing the extraordinary detail and skill of the modellers with the lighting and camera set ups. Museum of Modern Art New York. Image Emile Askey |

.jpg) |

The many faces of Pinocchio, at the Museum of Modern Art's New York Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio show. Image: Emile Askey |

.jpg) |

Shadow machine. Columbina Production Puppet. 2019~2020. Steel, wire, resin, paint, fabric, brass. 8.9 x 8.9 x 22.8 cm. Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio 2022. Image courtesy of Netflix |

Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio runs from December 11, 2022 – April 15, 2023, Floor 2, 2 South, The Paul J. Sachs Galleries of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Thursday, 15 December 2022

‘A three-storey, luminous birdcage with suspended hanging gardens and an extensive crypt below’: Sydney Modern is open at last

The Sydney Modern Project had the odds stacked against it since its inception in 2013. It has surely been the most controversial state gallery extension to be built in Australia.

Michael Brand – a Canberra-born, ANU and Harvard trained art historian with an outstanding museum career in Australia and America – was appointed as director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2012. This was on the retirement of Edmund Capon, who held the post for the preceding 33 years.

Brand launched the unfunded plan for a new building in 2013, the Tokyo firm SANAA won the architectural competition in 2015 and construction commenced in 2019 with a budget of A$344 million. The knives were quickly out for Brand and his project.

Some, like Paul Keating, did not like the location and called it a “gigantic spoof”.

Others did not like the design; a book was published by a former gallery employee attacking the project; and the new culture at the gallery. Prominent people in the Sydney art scene lined up to attack the project and the director.

There were some people who simply did not like Brand. He is a reserved, scholarly individual with a brilliant eye, in total contrast with the flamboyant, media savvy Capon.

There were faults with the original architectural design and significant modifications were implemented before construction commenced.

There were also external circumstances that impacted on the project: the murky world of NSW state government politics, bush fires that shrouded Sydney in smoke, COVID-19.

However, Sydney Modern, now that it is open, is a spectacular achievement. The floorspace of the gallery has almost doubled, creating a gallery precinct (Brand prefers to call it a “gallery campus”) with two buildings connected by an art garden.

On one side we have the stately neo-classical building that looks like a traditional 19th century art gallery with a series of extensions by Andrew Anderson, on the other side, a new 21st century structure.

A luminous birdcage

The new building may be described as a three-storey, luminous birdcage with suspended hanging gardens and an extensive crypt below. The main architectural concept is that of three limestone-clad, cascading pavilions leading down towards the water with a huge supporting rammed earth wall.

Below is the crypt, locally called the “tank”, in recognition of its origins as a fuel storage reservoir secretly and speedily constructed at the start of the second world war to store fuel for Allied shipping.

It reminds me of the huge water cisterns in Istanbul constructed by the Byzantines to store water for the city.

The tank is presently occupied by Adrián Villar Rojas’ “time-travelling sculptural forms” dramatically lit by constantly changing light sources. The smoke and mirrors display is deliberately disorientating, evoking more of a mood than a visual assessment of the artwork.

In the upstairs birdcage, it is very easy to orient yourself and be aware of your location and the various possible exits. In the crypt all is murky and unpredictable as you gradually negotiate the spaces and dodge the pillars and protruding sharp edges of the sculptures.

Indigenous art at the heart

Although there is an emphasis on Indigenous art with the transfer of the Yiribana Gallery from the basement of the old building to the entry gallery of the new one, this is more than simply a symbolic gesture to have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the heart of the gallery.

Indigenous art is found at all levels of the new building and is integrated into the display of non-Indigenous Australian and international art.

One of the highlights for me are the newly commissioned woven metal pieces by Lorraine Connelly-Northey. Her huge metal handbags made from discarded, well-weathered metal sheets from the outback have a stark sense of presence and are laced with wit.

Her work looks out onto the most ambitious project, the sprawling art garden by Jonathan Jones scheduled to open mid-2023.

Less a deliberate policy and more as part of the process of what Brand describes as selecting the most interesting new art, women artists make up 53% of the 900 exhibitors in the new building.

The major thematic groupings, or exhibitions, in the new building are Dreamhome: Stories of art and shelter, Making worlds, Outlaw and Rojas’s The end of imagination in the crypt. These will remain in place for the next six months before there is a new set of exhibitions.

An elegant build

Despite the slings and arrows, Sydney Modern (now known somewhat unimaginatively as the North Building of the Art Gallery of NSW) has come to fruition.

Possibly not the most magnificent art gallery in the world, as the NSW premier and his arts minister spruiked at the opening, but an elegant, formidable and very functional new building.

Politicians in Australia have always been very good at throwing money at new buildings, the true test will come if this doubling in size of the gallery will be accompanied by a substantial increase to the operating budget of the institution.

With new gallery spaces projected for Melbourne, Adelaide and possibly Canberra, funding is required for more than rammed earth, glass, bricks and mortar. Australia does not need a stampede of white elephants. ![]()

Sasha Grishin is Adjunct Professor of Art History at the Australia National University

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.

Friday, 9 December 2022

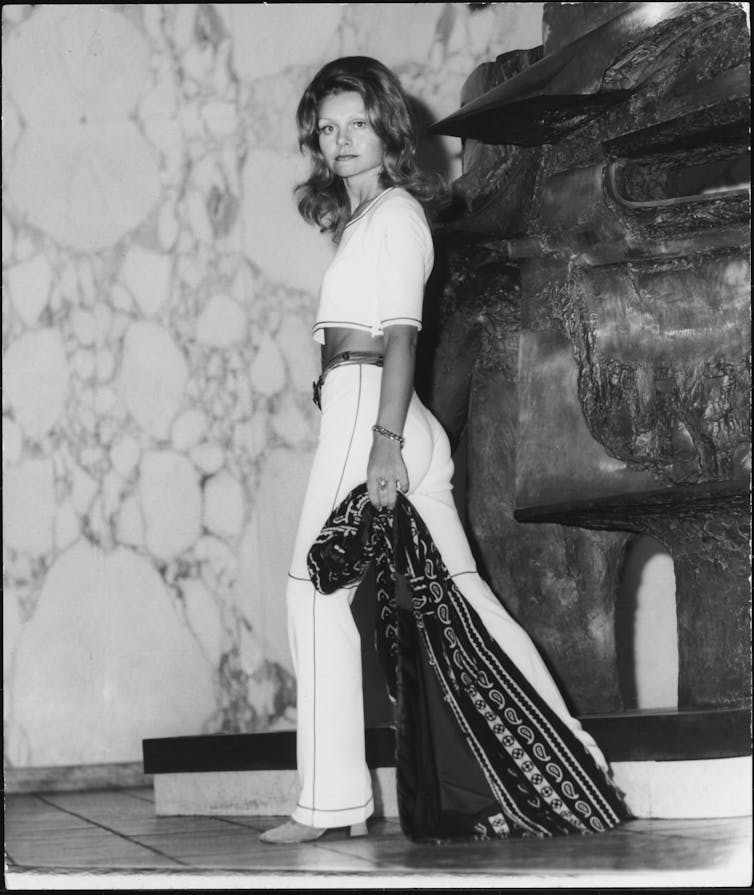

Clothes women wanted to wear: a new exhibition explores how Carla Zampatti saw her designs as a tracker of feminism

The late Carla Zampatti is celebrated in a splendid retrospective Zampatti Powerhouse at the Powerhouse Museum. Planned well before the fashion designer’s untimely death last year, the unveiling of her legacy will be bittersweet to her many fans.

Zampatti is often referred to as “Carla” by friends and those who worked for her, rather than her brand name, Carla Zampatti. Here, the simple name “Zampatti” removes the emphasis from Zampatti as designer to a simpler assertion: businesswoman, mother, philanthropist-entrepreneur.

It is a move as deft and elegant as the rest of the exhibition choices.

In one of the best-looking fashion exhibition designs Australia has seen, creative director Tony Assness serves up a dynamic vision of clothes punctuated by a vibrant red (one of Zampatti’s favourite design choices) that encourages excitement and discovery. Clothes are arranged by themes – jumpsuit, jungle, graphic, blouson, power – rather than date.

Curator Roger Leong leverages his years of experience to do a relatively new thing for Australian museums: tell the stories of clothes through the stories of women who wore them.

A migrant story

Zampatti’s story is an Australian migrant story. Born Maria Zampatti in Italy in 1938 (not 1942, as is often believed), she did not meet her father, who had migrated to Fremantle, until she was 11.

In Australia, she was forced to change her name to Mary. It was claimed the other kids could not pronounce Maria. She did not finish school. When she moved to Sydney in her late 20s, she reinvented herself as Carla.

The fashion business started on a kitchen table in 1965 under the label ZamPAtti. By 1970, Carla had bought out her business partner husband, and was sole owner of Carla Zampatti Pty Ltd.

Zampatti flourished in fashion. She had a finger on the pulse, was in the right place at the right time, and knew a more glamorous role was possible for a fashion designer than the industry “rag trader”.

In the 1970s, the markets suggested that the ultra-expensive haute couture was about to disappear, to be replaced by informal ranges created by a new type of designer often called a “stylist”. It was the decade of flower power, retro dressing and ethnic borrowings.

Until the 1960s, fashion had been dominated by the rise of haute couture and the “dictator-designer” system – mainly men who determined hem lengths and silhouettes for women. But in 1973, the French body governing high fashion added a new layer of designers, créateurs (literally “creators” or designers), who produced only ready-to-wear.

In 1972 Zampatti opened her first Sydney boutique, inspired by informal shops she had seen in St Tropez. Zampatti offered women bright jumpsuits, art deco looks and peasant-inspired ease.

She aimed to provide women clothes they wanted to wear. She draped the cloth and colours on herself. Like many women designers historically, she was alert to how her clothes made women customers look and feel. Zampatti remained the fit model for the whole range and would not produce anything in which she did not look and feel well.

Zampatti saw her “clothes as a tracker of feminism”.

The 1980s cemented Zampatti’s rise to prominence. She became a household name, even designing a car for women. In this time, personal expression became more important than unified looks dictated by designers. Zampatti’s Australian designing coincided with a new development in Italy: the stylisti. Small, focused family businesses alert to the zeitgeist and understanding quality flourished. It was an approach that emphasised quality and glamour.

Zampatti identified talent. She employed well-known couturier Beril Jents on the shop floor after she had fallen on hard times. She then employed Jents to improve the cut of her designs.

Zampatti continued to embrace the services of stylists and other designers including Romance was Born, whom she recognised could take her work to the next level.

The stories of clothes

Worn equally by politicians and their circles on the right and the left, Zampatti injected more than power dressing into women’s wardrobes. She inspired a sense that women wore the clothes, not the clothes them.

In this exhibition we are given many examples, from Linda Burney’s red pantsuit worn for her parliamentary portrait to a gown worn by Jennifer Morrison to the White House.

The exhibition viewer can turn from serried ranks of brilliantly styled mannequins and enter large “listening pods”, screening brilliantly edited videos in the manner of artist Bill Viola. The women, who include Dame Quentin Bryce and Ita Buttrose, discuss the creative mind of Zampatti or reflect on their own Zampatti wardrobe. They are amongst the best such “talking heads” I have seen in a museum.

Like many designers, Zampatti was not that interested in her own past. She did not keep substantial archives and records, which is a testament to the skills demonstrated by the museum in bringing us this show.

Zampatti never turned her back on her personal story, but she was a futurist, one who looked forward rather than backward.

Zampatti Powerhouse is at the Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney, Australia until June 11 2023.![]()

Peter McNeil, Distinguished Professor of Design History, UTS, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished with permission from The Conversation.

Subscribe to support our independent and original journalism, photography, artwork and film.